Picture by Debbie Hudson via Unsplash

Welcome to The Frontline. A fortnightly feminist publication for the 21st century. A place to find writing that speaks to you and about you, where women can feel connected and make new connections in a world that too often feels to have come adrift. A place where reality matters and women’s voices have power.

Why a regular feminist publication? Exactly a year ago today (30 May 2025), was publication day for The Women Who Wouldn’t Wheesht, the book we conceived and co-edited. When we embarked on the book, we had no idea what would happen. We did not know if a publisher would speak to us, let alone embrace the project. All we knew was that someone needed to gather together women’s stories of the campaign against the imposition of laws and policies in Scotland that erased sex in favour of gender self-ID. We wanted to make sure that the first draft of the history of this extraordinary period in recent politics was written by women who had been involved. Producing a Sunday Times best seller, as we did, was not on our agenda.

Energy of grassroots women’s groups

When the book reached its readers, we realised that we had struck a chord. Women from all walks of life wanted more opportunities to tell their stories, to talk about their hopes and fears, and the challenges that remain for women and girls navigating a world still largely shaped by men. When readers started asking about the next book, we quickly found that we wanted to give more women a voice, but in a different, less fixed and more open format. To do something more in the spirit of the many grassroots women’s groups that have emerged in the last decade.

Scotland’s second wave feminists inspired us. In 1978, the feminist magazine MSprint hit the streets. In our next edition (6 June), Marian Keogh, a member of the MSprint collective will describe what it meant to be on the frontline of women’s rights in the late 1970s and how things have changed, or not. To honour the tradition of more conventional women’s magazines, there will be a “free gift” for every Frontline reader, a link to a digital copy of the first edition of MSprint.

Women’s bold voices

Like MSprint and other second wave feminist magazines such as the mothership Spare Rib, The Frontline will be a bold, unapologetic publication that allows women to share their stories directly with other women – to amplify the power of those women’s voices which are all too often excluded by mainstream political and state-funded civil society organisations.

The experiences shared may range from those of young women refugees fleeing the Taliban to older women coping with caring responsibilities and ill-health. Women of all ages will explore issues relevant to their lives, from political representation to porn culture. We also want to build an accessible archive of first-hand accounts of women's struggles for their rights, from the last century to the present.

Above all, our Women on the Frontline essays will be a space for women to tell their personal stories, to share with other women their experience of being a woman in the first half of the 21st century. This is a publication where women can talk to each other about the issues that matter to them.

There will be regular features too, including Woman of the Week by Lily Craven – whom some of you may know as @TheAttagirls on Twitter/X. In this launch edition, she explains why remembering women’s history is a radical act. As editors, we will bring you Power and Policy, a watching eye on relevant developments in the world of politics and government in Scotland and the wider UK. As we progress, we hope to add interviews, feminist history, book reviews and your photographs. We want to celebrate women’s boundless creativity, as shown in the recent resurgence of feminist art used by women’s rights campaigners.

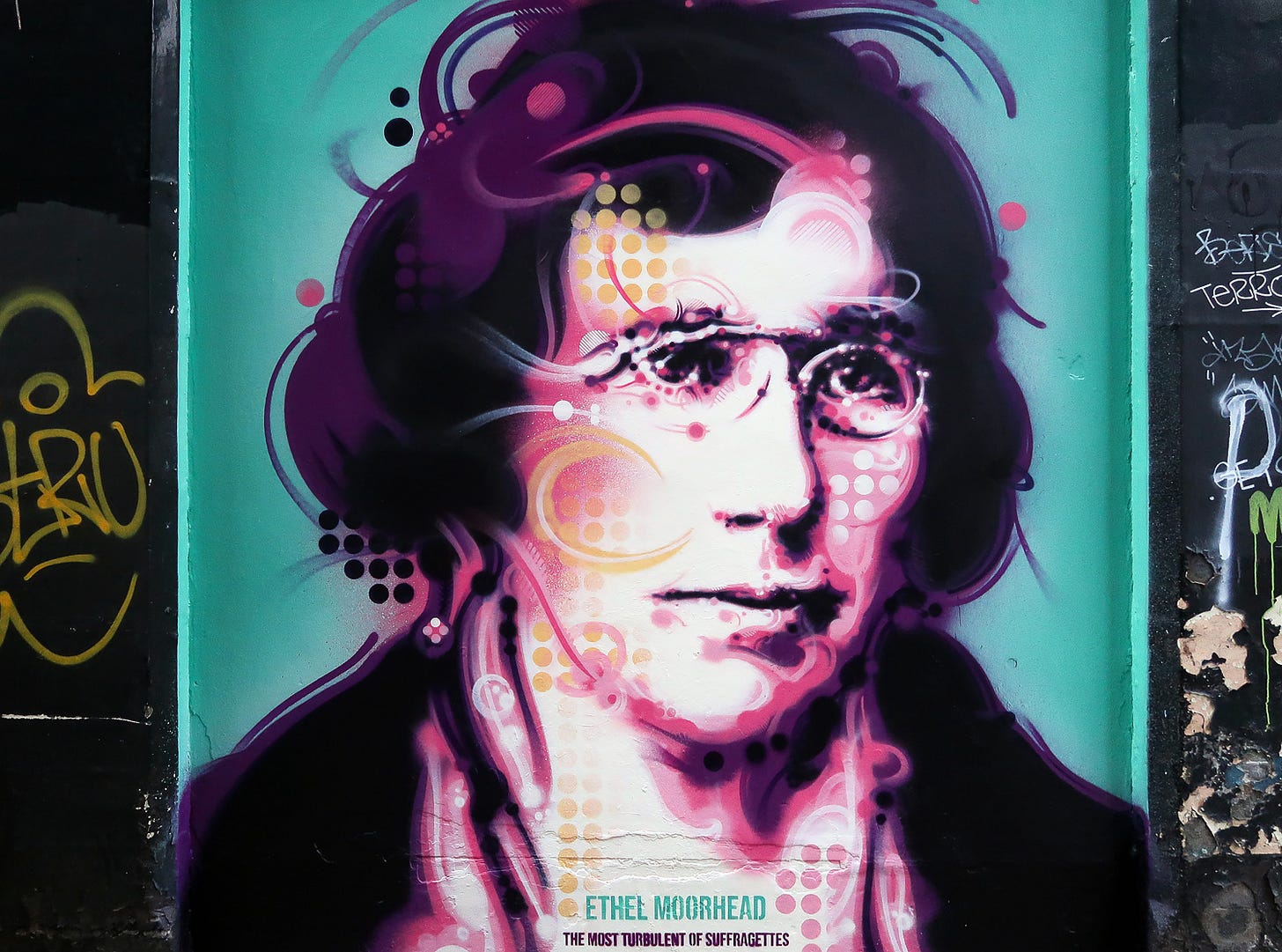

We named our embryonic publishing company Ethel Writes, in honour of Scottish suffragette and publisher Ethel Moorhead (and also after Lucy’s less militant suffragist grandmother). So for this launch edition we asked Prof. Sarah Pedersen to write about Ethel Moorhead, one of Scotland’s most combative campaigners for women’s right to vote. Later, after moving to Paris, she became a magazine publisher. The first edition of her magazine This Quarter featured, among others, Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound and James Joyce.

The Women Who Wouldn’t Wheesht may have been produced in Edinburgh but it was written for women across the UK and beyond. (Pic by Trina Budge)

The advance for The Women Who Wouldn’t Wheesht, a tiny fraction of the sum given to a well-known ex-First Minister for her memoir, was shared among our many contributors and ourselves as editors. Though some chose to waive their fee, we did not want to ask anyone to do yet more unpaid labour. Then, as we said in the book: “Profits from this book will go to organisations helping those women and girls elsewhere in the world who are currently among some of most silenced. We would like to be able to name these organisations without causing them problems. The reason we cannot do so is in this book. We look forward to the day we feel we can.”

The success of the book means that we are delighted to have begun to honour that commitment so soon. This means, however, that The Frontline must finance itself.

It remains very important to us that each woman we commission is paid for her work, and that that work is presented well. So we would like to thank our founding members, a couple of dozen people willing to give a modest amount each, who have allowed us to get the publication off the ground. We hope to repay their faith in us, and their commitment to women’s rights.

No paywall

As we move ahead, it is important to us that The Frontline has no paywall. Women remain more likely than men to be low earners or unpaid carers, and to have less to live on in retirement. So it was an easy decision for us that the full content should be free for those who are unwaged or on a low income.

For those who can afford to pay, our monthly subscriber fee is £5. An annual subscription offers a 17 per cent discount, at £50 a year, and there is a special founding subscribers’ rate of £100. Those who can afford to pay will be helping to keep the full content open to those who cannot. We will trust our readers to decide into which category they fall.

Our next edition is on Friday 6 June and fortnightly thereafter. Welcome to The Frontline, harnessing the power of women’s voices.

The Women Who Wouldn’t Wheesht

The book, which charts the battle for women’s rights in Scotland, was published a year ago on 30 May 2024. As editors we would like to thank the courageous women who wrote an essay, were interviewed for the book or supplied a photograph; every woman who campaigned; and every person who has bought, borrowed or lent the book, whether to read or listen to it. You can buy a copy here.

Ethel Moorhead: A savage suffragette

By Professor Sarah Pedersen

Mural of Ethel Moorhead in her home town of Dundee: Picture by the artist Michael Corr

In 1912, a well-dressed woman in her 40s entered a classroom at Broughton High School in Edinburgh and proceeded to assault the mathematics teacher, Mr Ross, with a dogwhip. She was dragged off Ross, a well-known volunteer for the Liberal Party, taken to the police station and placed in a holding cell. The prisoner then tried to bite an officer, threw herself to the floor and broke the cell windows by throwing her shoe at them. Shortly afterwards she was liberated on bail.

This woman was Ethel Moorhead, one of the most notorious Scottish suffragettes, whose exploits were reported by the press in tabloidesque tones of horror and excitement. Headlines of her exploits described her variously as a ‘Savage Suffragette’ or the ‘Screeching Suffragette’.

This was not Ethel’s first tangle with the law. A talented artist, who had spent time in India and South Africa as a child following her Irish army surgeon father, Moorhead joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (the Suffragettes) in 1910. Her family had settled in Dundee and Moorhead first became known to newspaper readers when she threw an egg at Winston Churchill, MP for the city.

A life of activism

Throwing herself into a life of activism, Ethel travelled to London to smash windows in spring 1912. By August, however, she was back in Scotland where she smashed the glass case around the sword at the Wallace Monument in Stirling. On arrest, Ethel gave the false name of Edith Johnston and was sentenced to seven days imprisonment in Perth prison. In January 1913, Ethel’s disruption of a meeting held by Prime Minister Asquith, subsequent breaking of windows at Leven police station and assault on a police sergeant by throwing water over him was reported under the name ‘Margaret Morrison’.

Ethel’s acts of window-smashing, disruption of meetings and arson continued until the outbreak of war, although connections were not always made between her individual acts by either the press or the police because of her use of pseudonyms. At the same time, she continued to exhibit her paintings, which were often commended in the same newspapers condemning her militancy. Ethel also sent letters to the editors of Scottish newspapers, demonstrating a thoughtful and engaging style that challenged those who condemned suffragette militancy. In comparison to her use of pseudonyms when arrested, she publicly identified herself in the newspapers as a militant and defiantly argued her case with her detractors.

Hunger strike

In July 1913, ‘Margaret Morrison’ and Dr Dorothea Chalmers Smith, wife of the minister of Calton Parish Church, were arrested on suspicion of attempting to set fire to a Glasgow mansion. Both women went on hunger strike while detained and were released by the prison authorities – Scotland not wishing to follow English prisons’ force-feeding of suffragettes. The Reverend Chalmers Smith later divorced his wife.

While Ethel was often identified as the ‘leader of the Scottish suffragettes’ in the press, she did not in fact hold any such role. In addition, some of her actions – particularly attacks on cultural icons – alienated some Scotswomen. This unhappiness deepened in July 1914 when Fanny Parker, the niece of Lord Kitchener, and an accomplice, heavily suspected to be Ethel, attempted to burn down Burns Cottage. Scottish suffragettes tried to disassociate themselves from actions that were perceived to be attacks on the nation by highlighting the suspects’ non-Scottish origins.

By this point, Ethel had established a pattern of arrests for attacks on politicians and property, smashing up cells, and then going on hunger strike. Released under the so-called ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ to regain her strength, she would then go on the run, using different pseudonyms, rather than be rearrested and returned to jail. But the authorities’ patience was about to snap.

First to be force-fed

Ethel was arrested for the final time in Peebles in February 1914. Suspicions had been raised by the behaviour of two ladies who wished to see nearby Traquair House. When the police arrived, one of them – ‘Mrs Marshall’ – was found to be Ethel, out on licence and on the run.

Returned to Calton Jail in Edinburgh, Ethel re-started her hunger strike. This time, however, the authorities refused to release her. Instead, Ethel became the first suffragette to be force-fed in Scotland. Perhaps due to the novelty of the operation, the force-feeding was botched, with the tube inserted into Ethel’s lungs instead of her stomach. She was released after being frequently force-fed, severely ill with pneumonia. Ethel’s condition caused questions to be asked in the House of Commons, but politicians were assured that her ill-health was not caused by the force-feeding, but instead by the prisoner’s habit of smashing all the windows in her cell.

On the outbreak of war, a truce was declared by the Suffragettes, many of whom threw themselves into war work. Ethel and Fanny Parker became involved in running the Women’s Freedom League National Service Organisation, whose aim was ‘To put the Right Woman in the Right Place’, and to secure well-paid work for women as replacements for men going to the front.

Magazine editor

After the war, Ethel re-engaged with her painting and moved firstly to Dublin before settling in Paris in the 1920s. Using money that she had inherited from Fanny Parker, she founded and co-edited the modernist literary and art journal, This Quarter, with the American poet Ernest Walsh. The journal published some of the leading artists and writers of the time, including Ernest Hemingway, Wyndham Lewis, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and James Joyce. The first issue of the journal included several of Ethel’s own paintings and in the second issue she published a lightly-disguised autobiographical account of her time as a suffragette, including a description of ‘Fan’ and ‘The Mouse’s’ attempt to burn down a church.

Ethel died in Dublin in 1955. A plaque to her was erected by Dundee Women’s Trail on King Street in 2008, while Ethel Moorhead Place is part of a residential area in Perth city centre. No smashed windows are recorded at either site.

You can read Mary Henderson’s biography of Ethel Moorhead here

You can see Michael Corr’s fabulous mural of Ethel in Albert Street, Dundee

Atta girl! : Introducing the woman of the week

By Lily Craven, known to her many fans on Twitter/X as @TheAttagirls

No one really knows who first said, “History is written by the victors” but I’d bet Grand National odds it was a man.

Think of your schooldays and count the number of times you learned about the role played by women in shaping history, other than regnant Queens and perhaps Marie Curie and Florence Nightingale. Yet women lived, worked, networked, debated, campaigned, organised, invented things and built them too - but you’d never know if your lessons, like mine, were confined to history books.

For a practical example, just look around you. Fridge, washing machine, dishwasher, ironing board, home security system, call waiting system, car heater and windscreen wipers, even the very first computer algorithm: all invented by women.

Are you surprised? Confined to the house, denied access to higher education, barred from engineering, denied entry to all branches of science and the professions for centuries, those bright analytical minds turned their attention to their immediate surroundings and saw what they needed to free themselves from domestic drudgery.

The Matilda Effect

In return, history ignored women’s achievements, glossed over them, or consigned them to dusty footnotes. If all else failed, their work was credited to - or stolen by - men, the phenomenon known as the Matilda Effect.

This was first identified by feminist Matilda Joslyn Gage in 1870 and named for her in 1993 by historian Margaret Rossiter, who said: “It is important to note early that women’s historically subordinate ‘place’ in science was not a coincidence and was not due to any lack of merit on their part. It was due to the camouflage intentionally placed over their presence in science.”

Once you see it, you cannot unsee it - the Matilda Effect is everywhere - but now substitute ‘history’ for ‘science’. The proposition still stands. What I do is pierce holes in that camouflage by writing about the almost-invisible women of history who overcame manmade barriers and changed the world.

Second-wave feminist

What started it was the outrage I felt when a woman of 60 was assaulted in 2018 by a man masquerading as a woman. The judge instructed her to refer to her attacker as “she”. That’s when my eyes opened to the madness overtaking organisations at national and local level.

As a second-wave feminist, I thought we’d won all the big battles, that it was just a matter of mopping up resisters and dragging them into the 20th century. Yes, I’d fought for female-only toilets in male prisons and kicked back against a ridiculous uniform code that required female prison officers to run to incidents in the prison in skirts and high heels (trousers were “unladylike”). I was more than a little irritated about being one of the few women in a roomful of senior prison managers, so I encouraged, mentored and promoted other women to try and redress the balance. Exactly what you might expect of someone who’d always regarded herself as a feminist.

But how had I managed to miss the barefaced theft of our words, our spaces and services, our sports? How had we suddenly been reduced to a walking collection of body parts?

It was a wake-up call.

Damage of sexist stereotypes

Once I saw, I couldn’t unsee the terrible damage being done to girls and young women who did not conform to offensive sexist stereotypes imposed on them by men try to copy women and their inane cheerleaders. It made me fearful for my little non-conforming nieces. They needed to see strong women as role models, women who didn’t care about performing femininity, who defied convention and did things their way. If you can see it, you can be it.

I went digging around in those dusty footnotes, found a little gold and started from there. I told my nieces the thrilling tales of women who were inventive, resourceful, and brave. Then I started sharing what I found more widely, tied to the calendar as Woman of the Day.

How do I find them? Often by chance. I go looking for one woman, spot a few more along the way - women whose stories really resonate with me - and file them away for the right time. Women’s history had been right under my nose the whole time. I just hadn’t realised that you needed to dig a little. The rather unexpected bonus was that in giving them a voice, I found mine.

I am a conspicuously law-abiding woman, a former prison governor, and if you had told me on the day I retired that one day, I’d be standing outside a police station in protest at the hounding of gender critical women, singing “Go catch some rapists” to the tune of Guantanamera, I’d have advised you to seek immediate medical attention for the effects of the bump to your head. But here I am, telling women’s stories and, behind the scenes, pursuing a second career as a women’s rights activist. I won’t fall asleep at the wheel again.

For this exciting new publication, I intend to find more women in history hiding in plain sight and write about them as Woman of the Week - but for now, I leave you with this thought from the 1949 memoirs of Somerset suffragette Nelly Crocker (1872-1962):

“Modern young women seem unaware of the price paid for their political and social emancipation and modern historians have greatly ignored the struggle.”