ISSUE 7: The Frontline

A 21st century feminist publication where women's voices have power

Pic via iStock

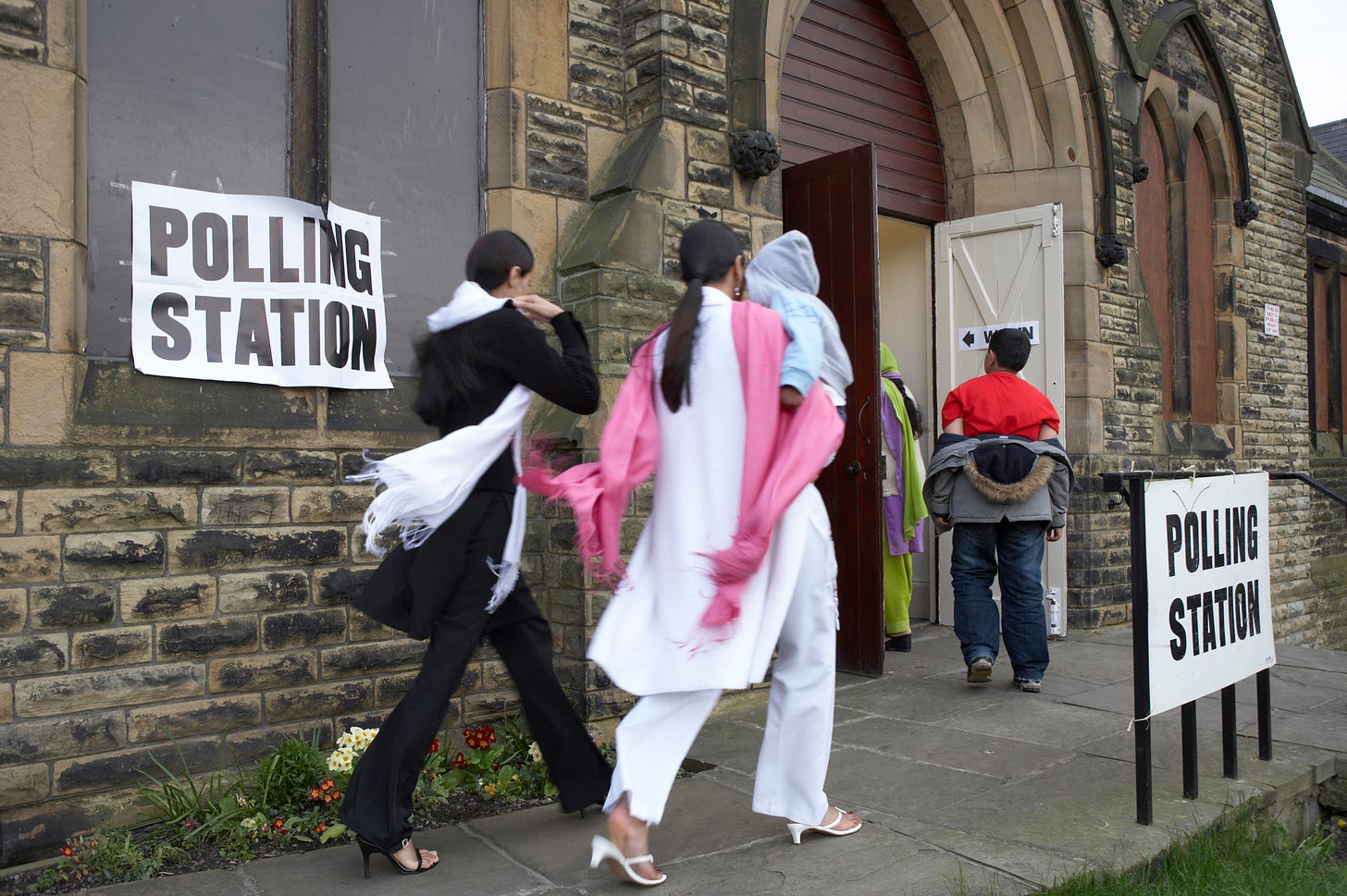

As parliaments across the UK reconvene after their summer holidays, the latest issue of The Frontline is a bumper edition looking at women in politics.

Joani Reid MP writes about her first year as an MP and the importance of class when fighting for women’s rights. It’s a powerful piece which every women who describes herself as a feminist should read.

Ash Regan MSP tells The Frontline why her Unbuyable Bill, to reform the law on prostitution, is long overdue and why passing it should be a priority for the Scottish Parliament, ahead of its next elections in May 2026.

Also on the frontline of elected politics, Pam Gosal MSP explains how she has worked with survivors and organisations to build support for her bill which seeks to reduce incidents of domestic abuse, including by tackling re-offending. This is also now before the Scottish Parliament.

Johann Lamont, a former leader of Scottish Labour, brings two decades of working across the chamber from Nicola Sturgeon to her informed review of the former First Minister's recently-published memoir.

And in keeping with our theme, our woman of the week is Frances Perkins, the USA’s first female Secretary of Labour, who introduced the 40-hour working week and social security for workers.

Finally, we use our regular Policy and Power slot to look at a headline-grabbing report on the experience of women seeking election, published recently by Engender, Scotland‘s government-funded feminist organisation.

The thread running through Issue 7 is the importance of women taking their place as elected politicians. We are half the population, so it’s a matter of a simple fairness that we should be equally represented in the corridors of power. As Ruth Bader Ginsburg said, "Women belong in all places where decisions are being made."

But that is not the whole story. As a former member of the Scottish Parliament Elaine Smith argued in Issue 5, it took the election of a substantial number of women to create protections for breastfeeding in public. Not all women will use their time in office to improve women's lives, but politics that does not give women our place will always be a disaster for us, as our last issue on the plight of women and girls in Afghanistan showed only too starkly.

The button at the end of this issue takes you to our subscriber chat. As ever, you can also find us in real time on X/Twitter, at @DalgetySusan and @LucyHunterB, and our shared account @EthelWrites.

We are delighted that we can now plan for our fortnightly 21st century feminist publication to remain fully accessible. But we depend on some of our readers becoming paid subscribers so that we can pay our contributors, as well as keep the newsletter free so ALL women can access it. If you can afford a paid subscription, please consider getting one. Thank you.

Feminists can’t ignore class because until we fight for ALL women then feminism is just privilege dressed up as progress

By Joani Reid MP

Pic via www.joanireidmp.co.uk

Fourteen months ago, I walked into the Commons chamber for the first time as the newly-elected MP for East Kilbride and Strathaven. I knew the job would present challenges in balancing parliamentary duties with family life, not uncommon for working mothers across the country. What I hadn't anticipated was how much this first year would teach me about the intersection of sex and class in ways that too rarely get discussed in political circles and how the prevailing "progressive" orthodoxy isn't just disconnected from ordinary women's lives, it's actively damaging them.

I've experienced the well-documented difficulties female MPs face: death threats, relentless social media abuse, family life disrupted. The personal costs are real, but it remains an enormous privilege, and I'm acutely aware of my advantages compared to most of the women I represent. Unlike most workplaces, Westminster is remarkably supportive of women - the institution understands misogyny and provides the systems and resources to support us. There is also genuine cross-party sisterhood, epitomised by the gender-critical movement. Our problems as female MPs are taken seriously. It's ordinary women outside these walls who lack this support, and too many on the political left have abandoned them entirely.

A deep rooted classism that targets women

The statistics tell part of the story: soaring single-parent poverty, a broken child maintenance system, the gender pay gap, increasing sexual crime and soaring domestic violence. But the discrimination cases crossing my desk reveal something deeper: Scotland faces deep-rooted classism specifically targeting women.

Our public institutions confront rather than support, dismiss rather than listen to working-class women in ways they simply do not with men. I've witnessed systems deliberately grinding down women who can't navigate bureaucratic mazes, in the hope or indeed knowledge they'll eventually give up. Whether it's schools, crime or children's services, these women lack the time and skills to fight back. When the few who do reach out to seek my advocacy, we can overturn these blatant injustices relatively easily. The cases that never cross my desk are what haunt me.

A working-class mother faces teachers who assume her child's problems stem from poor parenting, social workers who scrutinise her home with judgemental eyes, and education authorities who offer criticism and disdain rather than solutions. When she complains, she's dismissed.

The same woman presenting at A&E with concerning symptoms will wait longer, be taken less seriously, and have her pain dismissed as attention-seeking or "lifestyle-related" in ways that simply don't happen to women who arrive in cars rather than on buses, who speak with the right accent and understand how to navigate professional hierarchies. Children's services provide perhaps the starkest example: a well-spoken, well-presented mother might receive family support when struggling, whilst her working-class counterpart faces immediate suspicion, intrusive questioning, and the implicit threat that her children might be removed.

The most egregious example came through my Home Affairs Select Committee work. Listening to the formidable Alexis Jay and Louise Casey revealed that sexual abuse and exploitation victims were overwhelmingly working-class girls whose voices went unheard because they didn't fit the right profile. The same pattern emerges in online safety: middle-class families can monitor their children's internet use, whilst working-class kids face greater exposure to harmful content. Class determines not just opportunity, but safety itself.

A betrayal of the most vulnerable women

Working-class women understand instinctively why women's spaces and safeguarding matter. I haven't met one woman on the doorstep who considers gender ideology as anything other than dangerous and peddled by those who don't grasp the realities facing non-privileged women. Yet women of the so-called left, elected representatives no less, fight against single-sex spaces whilst championing sex workers' rights to "live as they choose."

These same people of the left actively choose to protect their ideological privilege over the safety of vulnerable women in prisons, refuges and hospital wards. It's a betrayal that would be unconscionable if it weren't so predictable from those who claim to champion the oppressed and vulnerable.

Contemporary progressive politics has become utterly disconnected from ordinary women's lives. When we talk about "leaning in" or breaking barriers, it's too often from politicians or activists who can advocate for ideologically fashionable positions without facing the practical consequences. It's working-class women who live with the reality of these decisions.

Working-class women face a double bind rarely acknowledged by the left "progressives" claiming to represent them. Fighting both sexism and class prejudice without resources or networks, they're systematically failed by institutions. Their voices carry less weight, their experiences dismissed more easily, their safety matters less to those in power.

My first year in Parliament has shown me that discussions of sex and class cannot be separated. They're intertwined in ways that disadvantage the most vulnerable women whilst privileging those with existing platforms. The women's rights movement must reckon honestly with this reality.

The women in my constituency who clean offices at dawn, work multiple jobs, face impossible choices between safety and security - their experiences matter a great deal. But they're not setting the left's agenda because they lack time, resources, and cultural capital. So we must. This means confronting self-proclaimed progressives, particularly within our own circles.

Until we acknowledge this honestly, we're only fighting for some women, not all. And that's not feminism but privilege dressed up as progress.

Joani Reid is the MP for East Kilbride and Strathaven. A graduate of Glasgow University, she was previously Head of Policy for the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and served eight years as a councillor. Click here for more information.

Unbuyable: As police statistics show a 70 per cent rise in prostitution crimes Ash Regan MSP is determined to end the shameful exploitation of women

Pic via Nordic Model Now

Ash Regan MSP is a woman with a mission: to end the purchase of sex in Scotland. She won the right to introduce her Members’ Bill (similar to a Private Members’ Bill at Westminster) in February this year. The Prostitution (Offences and Support) (Scotland) Bill is now in the first of three stages.

In the new session of the Scottish Parliament, which starts next week, the Criminal Justice Committee will scrutinise the draft legislation, and it is currently seeking views from members of the public and organisations. The deadline for submission is 5 September, so there is still time to tell the committee what you think. The call for views is here.

Earlier this week, Scotland’s latest crime statistics showed a rise in incidences of rape and sexual crime and a 70% rise in prostitution crimes.

Speaking to The Frontline Ms Regan said: "These stark figures show, with absolute clarity, that laws, including those on prostitution, only work effectively when they are enforced effectively. Police Scotland announced recently that they have expanded Operation Begonia, which began as a pilot in 2012, as a national strategy to address on-street prostitution. Yet we know an estimated 90% of prostitution now happens behind closed doors, where the exploitation of children, trafficked women and other vulnerable people fuels a growing online marketplace for those who believe that financial or other compensation can replace free consent to normalise their perceived right to buy sex.

"Scotland's current legislative approach is outdated and leaves vulnerable women and men exposed to harm. We must understand how these figures break down between those exploited in prostitution and those who exploit others. It is well understood that the profile of those exploited in prostitution is harrowing, and my Unbuyable Bill crystallises the differences between the exploited and exploiter in law by switching criminality to the buyer and providing the right to support for the seller.

“The focus of this debate must move to the buyer as my bill seeks to criminalise the purchase of sexual acts. No one is entitled to elicit unwanted sex, yet where are the men coming forward to debate what they currently see as their 'right to buy'? If they will not come forward into the public debate, I think we can conclude that their perceived right includes their privacy as a purchaser of sex - this is hardly the hallmark of a ‘normal commercial activity’.

"The harms to those caught up in this dangerous and harmful life exploitation are well documented and survivors do not exit the sex trade without consequences, including complex PTSD, leaving them in need of the right package of support and care to recover their lives. The right to support is a core pillar of my bill.

"If the SNP government's own words on their commitment to address the escalating crisis of male violence against women and girls mean anything, they must tackle it at its roots. Until Scotland follows Sweden and an increasing number of countries across the world by criminalising the purchase of sex, driving the normalisation of the objectification of women and desensitising the harm of the sex trade, we will never deliver true equality of the sexes. The message must be clear: women are not for sale - sex in Scotland is unbuyable."

"We must reframe the shame, not on the exploited but on the buyers and profiteers of this global trade built on exploitation and harm. Anything less betrays our next generation."

Ash Regan MSP has been the member for the Scottish Parliament for Edinburgh Eastern since 2016. She served as Minister for Community Safety from 2018 until 2022 when she stepped down in a protest over the Gender Recognition Reform Bill. She left the SNP in 2023 to join Alba.

How survivors of domestic abuse have been given a voice in shaping legislation to go beyond prosecution and into prevention

By Pam Gosal MSP

Pam Gosal MSP speaks to women outside the Scottish Parliament

The Prevention of Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Bill was introduced in May 2025 and aims to address the rising number of instances of domestic abuse in Scotland.

A growing problem

The latest Scottish Government figures show that in 2023-24 almost 64,000 instances of domestic abuse were recorded by Police Scotland - one incident recorded every 10 minutes. This figure represents a 3 per cent increase from the previous year, with a huge number of incidents attributed to repeat offenders.

Additionally, the number of number of crimes recorded under the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018 rose by 26 per cent in the latest fiscal year.

Giving survivors a say

I have drawn on my personal experience from childhood, when I would watch survivors of domestic abuse, from diverse backgrounds, enter my mother’s shop in Glasgow’s Argyle Street, seeking help and support. These survivors would rarely engage with the authorities and so the extent of the prevalence of domestic abuse was not recorded or understood at that time.

I wanted to ensure that my Bill represented the voices and experiences of the organisations that deal day-in and day-out with domestic abuse, as well as the voices of survivors. I engaged with them at every possible point. Specifically, I met with survivors and organisation on three occasions. Firstly in 2022, before the Bill was introduced, then in 2024, while the Bill was being drafted, and then again in 2025, after the Bill was published. My Bill represents the voices and expertise of those on the ground.

The Scottish Parliament’s formal consultation ran in 2022, and in July this year, the Criminal Justice Committee issued a call for views which closes on 15 September. You can make your views known here.

Engagement with organisations and survivors of domestic abuse has been key to getting the Bill to where it is now. I am pleased to say the majority of the organisations and individuals I have spoken with are supportive of the Bill’s general principles and some have provided suggestions on how to strengthen the Bill. It would not be where it is today without their help.

The aim of my Bill is to reduce the incidence of domestic abuse and tackle re-offending through a series of measures. It includes four parts.

A new system of notification

Part 1 introduces notification requirements for domestic abuse offenders, known as the Domestic Abuse Register, similar to the Sex Offenders Register. This means that convicted offenders must provide certain information to the police. They must also inform the police about changes to their circumstances if, for example, they change their address or their name.

The onus will be on the perpetrator to provide this information, as opposed to survivors having to provide information about their perpetrator to the authorities. The Register will work within the systems already in place, such as the Disclosure Scheme and with the agencies already working to tackle domestic abuse. The information provided will help authorities monitor the perpetrator, while the intent is for this Register to not only combat offending, but also to act as a deterrent. And failure to provide information and update it when it changes will be a criminal offence.

Assessment for rehabilitation after conviction

Part 2 introduces a mandatory assessment of whether a person convicted of a domestic abuse offence is a suitable candidate to take part in rehabilitation programmes or services. The offender’s suitability is to be assessed at three separate points. These are prior to sentencing, while the offender is in custody, and prior to the offender’s release.

Currently the Caledonian System, a court-mandated programme which works with men convicted of domestic abuse, is not available universally, even though the Scottish Government had promised that would be the case by 2026. This means the current system is somewhat of a postcode lottery.

The importance of data

Part 3 places a requirement on Police Scotland, the Crown Office and the Procurator Fiscal Service to collect demographic information. This includes the victim’s age, sex, disability and ethnicity. The Scottish Government would also need to publish an annual report on the data gathered. A voluntary element is also placed on charities to provide this information. As they are often short of resources, I did not make it mandatory, even though a lot of these organisations already collect more data that the authorities.

Robust data collection is important so that support programmes can be tailored to specific and diverse needs, as a one-size-fits-all approach does not always work.

Education is essential

Finally, Part 4 requires the Scottish Government and education authorities to promote, facilitate and support domestic abuse education in schools. Currently the provision of domestic abuse education is another postcode lottery, with no systemic approach or uniformity. That is why my Bill will create a requirement for domestic abuse education in statute.

In November 2024 I attended the BBC Radio 4 Reith Lecture with Dr Gwen Adshead. I asked her about the vitality of education in preventing domestic abuse, which features in my Bill. Dr Adshead agreed and stressed the importance of emotional education in schools, with the focus on managing relational conflict and emotional complexities while tailoring education to different age groups.

That is why I believe a proactive approach in teaching about domestic abuse in schools is important, so that children are taught to reject the thinking and behaviours that may otherwise eventually lead to them committing such crimes. It also equips them to identify what domestic abuse actually is, including conceive control as well as physical and mental harm. These conversations may not be easy, and need to be sensitively done. But it is essential that they are seen as a key part of reversing the worrying upwards trend in domestic abuse that I am determined the Parliament should address.

Pam Gosal MSP was elected as an MSP for West Scotland Region in May 2021 and made history as the first Indian Sikh MSP and one of the first women of colour elected to the Scottish Parliament. She sits on on the Equalities, Civil Justice and Human Rights Committee and the Economy and Fair Work Committee.

Frankly, Nicola Sturgeon’s memoirs reveal an unbending politician, one more interested in signalling her concerns than making change happen, and a woman devoid of the notion of sisterhood

By Johann Lamont

Pic by Iain Masterton www.iainmasterton.com

A great deal has already been said about this memoir, which is not so much an illumination of the challenges, compromises and privilege of power as a project in selling the author’s image of herself.

Any memoir is essentially individual in its perception of the world. Even so, I was staggered by the gap between the author’s truth and the real world as the rest of us may recall it.

Speaking this month at Glasgow University, Nicola Sturgeon bemoaned the lack of cooperation now in comparison with the early years of the Parliament. Really?

In the book she recalls the battle to repeal Section 2A (Section 28 in the rest of the UK) during the very early in the days of the Parliament when public support for this new institution was teetering under the weight of perceived uselessness and scandal.

The minister in charge, Wendy Alexander, was assailed by religious opposition and a campaign of ugly personal attacks by SNP donor Brian Soutar, amid the vicious misrepresentation of gay people.

And this advocate for co-operation? Did she support this female politician, resist the temptation to take party political advantage, protect the nascent Parliament against its critics, call out her SNP donor? No.

Bad enough that she led the political charge against Alexander’s proposals. Worse, her memoir explains that this was not her fault, but that of her boss. We can all reflect on past views we have come to disavow. But what is revealed here is utter cynicism, both then, in its execution, and now, in its justification.

A female leader full of contradictions about her support for women

The contradictions are plentifold. Here is a female leader who in leadership contests prior to her own never supported women candidates – and struck a deal with Alex Salmond to become Deputy Leader that skewered the leadership chances of Roseanna Cunningham.

A female leader who was absent during the tough campaigns for women’s representation in politics and who now seems unable to acknowledge how these benefitted her. As so many women throughout history have learned, personal striving and talent are rarely enough. And yet this is the story this memoir seeks to sell.

And while Nicola now disparages her erstwhile leader’s behaviour when he was her boss, there is no evidence of her taking to task the man she once described as being ‘without a sexist bone in his body’.

Sturgeon is not shy of humblebragging

Nicola of course is a debater who honed her skills at university, where debating points are more important than substance. She is not shy of reminding us just how brilliant she is, modestly referring to her anxieties and then recording in eyewatering detail any praise that is lavished on her. Humblebragging is a thread that runs through the book and her promotion of it, where even her imposter syndrome becomes more akin to imposter ‘imposter syndrome’ syndrome.

For someone keen to underline her own sense of duty and destiny, her persistent denigration of the motives of her opponents stands out. Most offensively, during Covid, when politicians are struggling to raise issues on behalf of anxious constituents, they are accused of ‘reverting to type’, making attempts to manufacture ‘scandals’ and ‘deliberately manipulating events to erode trust of the public in their government’. This from the woman who in opposition ill-advisedly lent her support to the "single vaccine" campaign, which contributed to anxiety about the MMR vaccine, while claiming to address it.

She embraced retail politics, even when she was all powerful within her party and the country. She resisted the precious opportunity such power allows to have a more mature and thoughtful dialogue about the challenges we face as a country.

Even post Covid, her manifesto offer was more free things – bikes and laptops among them - rather than serious plans for recovery. But then if you believe a box full of baby stuff means that all our children will have the same start in life, or your education failures are because you failed to grasp the impact of poverty on learning, perhaps that is no surprise.

Sturgeon’s reluctance to accept blame for gender battle

Thus in her own telling we see a reputation built on debating skills, not developing thinking. A politician who always assumes base politics in others. A women devoid, it would seem, of the notion of sisterhood. A leader unwilling in power to take serious decisions, highly invested in signalling concern rather than making change happen.

The last chapters of the book see these strands come together in the consequences of her proposals to change the 2004 Gender Recognition Act to include self ID.

I have to confess I could only read these chapters in highly rationed sections, interspersed with walks, making dinner and avoiding kicking the furniture.

First, I was struck by the wilful reluctance to address or even acknowledge the cause of so much public concern. Then by the presumably deliberate decision to make so many women invisible.

No mention of Joanna Cherry, a victim of criminal abuse; absent is Joan McAlpine who tested policy and gave voice to survivors of rape who were self-excluding from services because they were no longer single-sex; and unreferenced is Ash Regan, a government minister who resigned because of her fear of the consequences for women and girls.

No mention either of the ‘six words’ debate on forensic medical examinations, where the government was forced to back down in the face of internal opposition and a powerful external campaign.

Nor of her supposed flagship hate crime bill, which included protection for cross-dressers but not for women.

A First Minister who refused to engage with campaigners - who were not valid, homophobic, racist (insert the putdown of your choice) - now claims laughably that debate became impossible when a famous woman donned a t-shirt.

Instead of exploring the tensions and arguments, the former First Minister reveals herself as unbending. She does not show even a fleeting thought for why women, hitherto politically progressive and many committed to independence, might be so exercised that they would put themselves in political – and at times personal - harm’s way to get her government to change course.

Her conclusions? They could only be oppositionists, duped by or willing to support the far right. If straw manning were an Olympic sport, this chapter would see the author on the podium.

Nicola Sturgeon, ‘flexible’ and cynical and with politics seemingly rooted in nothing other than ambition, simply cannot understand those who showed her they did have a bottom line.

Her reaction to the emergence of Isla Bryson shows her true impulses. A double rapist, who transitioned after being charged, was to be placed in a women’s jail, the entirely logical consequence of her support for self-ID. As the story broke, did she pause and contemplate she might have been wrong? No.

She complains she was not warned about the case. And then grotesquely suggests that women saw it merely as a means of attacking her, without thought for Bryson’s victims nor for what he revealed about the consequences of her policies for women’s safety and dignity. Her desperate search for a form of words, her refusal to confront the possibility that she was wrong have resulted in tortuous, incoherent and offensive dissembling.

A career built on point-scoring

A lifetime of success predicated on point scoring rather than developing and reflecting on arguments led to her driving policy through that even she, with all her debating skills, could not – and cannot – explain.

The retail politician came up against women who were not buying what she was selling. Her decision to step down followed.

It is the richest of ironies that by her obduracy and reckless disregard, women across the political and constitutional divides came together, agreeing where we could, disagreeing respectfully where we could not, resulting in the burgeoning of a creative, informed, educated and challenging women’s movement. Scotland is much the richer for it.

As for Frankly? It is to candid self-awareness what a ferry with painted-on windows is to an islander’s transport needs. Says it all, really.

Johann Lamont is a former teacher, who was a Labour and Co-operative Party MSP, initially for Glasgow Pollock, from 1999 until 2021, when she stood down. She was Leader of Scottish Labour from 2011 to 2014.

Atta girl! Frances Perkins, born in 1880 in Massachusetts, was a lifelong campaigner for workers’ rights and the first woman to serve in a Presidential Cabinet. She was instrumental in establishing social security for American workers, a 40-hour working week and restricting child labour

By Lily Craven, known to her many fans on Twitter/X as @TheAttagirls

Pic by Kropewnicki via iStock

The young Frances Perkins went against the social conventions of her time and did what few young women did at the turn of the century. She pursued further education at Mount Holyoke College and learned about the dangers of sweatshop work and child labour.

Following graduation, she took up teaching but after volunteering at a settlement house - a place where poor people could access daycare, English classes, and healthcare - she visited tenements and her determination to fight for social reform was forged. Yet, reform requires power, and what can a woman do when she doesn’t even have the vote?

In 1910, Frances became head of the New York office of the National Consumers League where she campaigned for better working hours and working conditions, but it was the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911 that galvanised her, the same fire that spurred her contemporary, feminist and trade unionist Rose Schneiderman, to rip into affluent but complacent members of the Women’s Trade Union League.

Fire disaster killed 146 workers, most of them young women

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, still the largest industrial disaster in New York, broke out on the afternoon of Saturday, 25 March 1911 on the middle and upper floors of a building in Greenwich Village where poor working-class women toiled in the garment industry for 70 hours a week or more for peanuts.

It started with a small fire, just a small fire, in a scrap bin. The bin was wooden and contained several months’ worth of cloth scraps. It stood on a wooden table with huge mounds of scraps of cloth underneath and the whole thing was surrounded by hanging fabrics. All highly combustible material.

There were no sprinklers in the building. There were stairwells but doors were locked and blocked with machinery. The exit doors were locked and the windows leading onto the fire escape were rusted shut.

The fire spread and trapped the women on the 8th floor, where they jumped from the windows with their hair and clothing alight. Fire ladders only reached the 7th floor, so firemen held nets to catch them, but the nets tore apart. By the time it was over, 146 workers had died in horrendous circumstances, almost all young women.

Frances witnessed the women garment workers falling to the ground, and was so appalled she left her post with the National Consumers League to act as executive secretary to the Committee on Safety of the City of New York, formed by President Theodore Roosevelt specifically to improve fire safety.

She conducted investigations, took the commissioners on more than 50 field trips to visit factories, summoned witnesses to testify under oath and gave evidence herself, stating that the flames of the Triangle fire became "a torch that lighted up the industrial scene."

By 1914, 13 of 17 bills submitted by the Commission passed into law, including health and safety legislation, better fire safety, more adequate factory ventilation, improved sanitation, and machine guards. Frances was instrumental in persuading the New York legislature to pass a "54-hour" bill that capped the number of hours women and children could work, although she continued to push for an eight-hour day.

She spent the best part of two decades in New York politics lobbying for child labour laws and more stringent factory inspections, and when Franklin D. Roosevelt became Governor of New York in 1929, he appointed Frances as the New York State industrial commissioner with a staff of 1,800 and a political headwind that saw her deliver a 48-hour working week for women, a minimum wage and unemployment insurance laws.

First female Secretary of Labor

Weeks before FDR’s inauguration as President in 1933, he offered Frances the post of Secretary of Labor, a post never held by a woman. She thought about all of the things important to her, the principles she would never compromise - a federal ban on child labour, a 40-hour working week, minimum wage, health insurance, unemployment insurance - and said: “Nothing like this has ever been done in the United States before. You know that, don’t you?” FDR said he’d back her if she took the job. She took the job.

She was mocked by some US senators for not taking her husband's name. She was mocked by the press for her plain, no-nonsense image. She was mocked by her peers in the Presidential cabinet, some of whom acted like schoolboys and passed notes about her during Cabinet meetings.

Madame Secretary kept her cool, ran a tight ship, chaired the commission considering social security, managed the male egos around the table, and drafted the legislation herself. She knew that “the roots of social security stem from that deep well of charitableness that resides in the American people” and by 1935, FDR signed her Social Security Act. He called it “the cornerstone of my administration.” She saw it as “flat-footed first steps.”

By 1938, Frances had helped to cement into place the Fair Labor Standards Act, the minimum wage, overtime for 40+ hours a week and the first tough child labour laws. When Harry Truman took office in 1945, Frances’s tenure as Secretary of Labor ended, but she served on the US Civil Service Commission where she fought against discrimination in federal hiring. This remarkable woman died in 1965 at the age of 85.

In her misspent youth, Lily Craven spent 28 years in prisons in England writing risk assessments, operational orders and contingency plans. Now retired, she spends her time finding ordinary women whose extraordinary achievements were buried in dusty footnotes in history books and writes about those instead.

Navigate the public policy maze with the editors as they keep a watching eye on the issues affecting women

Pic by: akinbostanci via iStock

Scotland’s state-funded feminist organisation has a duty to support more women in politics but does its latest research take forward the arguments for women or try to dodge clarification of the Equality Act?

By Lucy Hunter Blackburn and Susan Dalgety

Pic via iStock

Engender began as a small volunteer organisation in 1993. It describes itself as “Scotland’s feminist membership organisation”. In 2023-24, its annual grant from the Scottish Government was worth over £550,000, more than triple its value in 2015-16. This provided 98 per cent of its total funding. It has eleven staff and specialises in “think-tank” type work; it has no service delivery role.

Engender’s manifesto for the 2026 elections, published this week, asks for “a new fund targeted towards women and underrepresented groups in politics to overcome barriers to political participation.” The wording might suggest Engender sees women as distinct from “underrepresented groups.” However, it goes on to note that just 35 per cent of local councillors are women (the figures are 45 per cent for MSPs and 40 per cent for MPs).

Arguing for this, it draws on its own recent report Women’s Political Journey, produced with assistance from three external consultants.

Feminist academics such as Professors Fiona Mackay and Alice Brown have spent their careers writing about and researching women in politics, including the age-old question: how to increase the numbers?

What does the Engender report add to this?

How many women, seeking election to what?

The research relies mainly on a small number (159) of self-selected returns to an online survey. There are lots of pictures, but the figures are often hard to unpick. Around one-fifth of respondents appear not to have got as far as putting themselves forward at all; others were not approved by their party as a potential candidate, or if they were, were not selected to stand. Reading between the lines, three out of five of those who responded to the survey (just over 90 people) appear to have made it as far as standing for election.

The only information provided on whether respondents’ experience was of local, Scottish Parliament or Westminster elections, and how recent it was, is in a pie chart which confusingly sums to 193 per cent, almost double what it should, making it impossible to interpret clearly. The text does not explain this further.

In addition, 15 women were interviewed. The report says this included only one Holyrood candidate (whether list or constituency is not stated), five with experience of seeking election to Westminster, and seven with experience of council elections. This is far out of kilter with the distribution of electoral opportunities and experience: there are 1,227 council seats in Scotland, 129 MSPs, and only 57 MPs. How far experiences differed for different levels of government is not discussed.

A more useful report would have been clearer about what if any differences it found in women’s experience in seeking election at different levels, and not relied on interviewees so heavily skewed towards the body furthest away, which offers the fewest opportunities.

An unrepresentative group, sex unknown

Four-fifths of respondents answered demographic questions. Of these, almost two-thirds were over 45. The sample was unrepresentative also on other characteristics, including caring responsibilities, self-declared disabilities, sexual orientation, and party membership. The report describes its sample as unrepresentative on ethnicity, although the data as shown suggests survey respondents were close to the general population there. The text of the report suggests some data on respondents’ social class was collected, but none is reported. Data was not collected on respondents’ sex. The results reported for “gender” suggest some survey respondents may have been male, but it is not clear how many.

Over-claiming from a small evidence base

The only figures given are as a percentage of those answering a particular question. So where the Engender manifesto says “Over 70 per cent of participants in our study reported experiencing online harassment during campaigns,” this means 70 per cent of all those respondents who answered that question. How many did so is not said. It appears likely however it was only asked of those who got as far as actually standing for election. If so, this significant and widely-quoted figure would be based on reports of online harassment from, at most, 66 self-selected online survey returns.

Research like this can offer a vivid snapshot of individual experiences and shed light on how processes work, or fail to. But as Joani Reid’s piece reminds us, we already knew, for example, that online abuse can be a real problem for women in politics (and sometimes, men; nothing in the report helps make cross-sex comparisons). This sort of research cannot add to our understanding of how common this or any other problem is, whose existence is already well-known.

The missing element: quotas

The report’s many recommendations miss one obvious proposal.

Back in 1993, a determined group of women succeeded in persuading the Scottish Labour Party to adopt women-only lists in some parliamentary seats. As Johann Lamont told the Herald at the time: ''We have been listening to the persuasion argument for a long time. It's not realistic to suppose you can persuade people out of power when they have always been there.''

Labour’s policy had a real impact on the new Scottish Parliament, that has persisted. But local government, which should be the most accessible tier of government for women, particularly those with caring responsibilities, continues to lag behind.

Local government is rooted in its communities. Councillors have responsibility for services that make a very real difference to women’s lives, from schools to social care, transport to the local environment. There should be far more women councillors, and there is a simple way to make that happen.

Legislative quotas are discussed, but in much softer terms than Engender has used when it has argued for these in the past. The recommendations are limited to promoting positive attitudes towards these.

Legally enforced quotas could transform Scottish local government. They may indeed be the only effective way to kick-start that change. Recent confirmation that quotas would require legislation at Westminster hardly matters: the research report includes some recommendations for the UK Government.

Engender’s position on quotas has, however, always been based on “gender identity” not sex. After years of ferocious advocacy here, has it lost its appetite for legal change, in favour of pursuing more loosely-defined cultural change initiatives, in the wake of the Supreme Court decision?

A missed opportunity

Engender has missed a huge opportunity with this report. Research like this adds modestly, at most, to the body of knowledge already out there on barriers to women’s participation in politics. Indeed, by making limited reference to the challenges faced by working class women, it actively reinforces the marginalisation of social class as an issue that characterises contemporary Scottish politics, to its shame.

Engender has the ear of ministers. It could have done something new and more substantial, perhaps advocating taking the fight for quotas to Westminster, rather than stepping back from its previous advocacy of them. It might have focussed specifically on local government where the sex imbalance is especially stark and where working class women have their best chance of entering the system.

Last, in publicising its findings as it did – an exclusive with The Herald was headlined “Major report reveals widespread sexism and abuse in politics” – it risks doing as much to deter women from political participation as to stimulate change. For that reason alone, with resources for think-tank work far beyond what many third sector bodies in any area could imagine, let alone grassroots women’s groups, Engender has a responsibility to produce more heavyweight research.

Northern Irish Assembly Recess dates: 5 July 2025 to 31 August 2025

Scottish Parliament Recess dates: 28 June to 31 August 2025

Senedd Cymru | Welsh Parliament Recess dates: 21 July to 14 September 2025

UK Parliament Recess dates: 23 July to 31 August 2025 (Commons), 25 July - 29 August 2025 (Lords). The Conference recess runs for four weeks mid-September to mid-October.