Pic by Nomcebo Mkhaliphi

We love words, but as women campaigners have known for a century or more, images have their own power, and this issue of The Frontline is rich with them.

Jenny Reilly, better known on Twitter/X as @crit_gen, writes about banner-making as her way of coping with a world gone mad. She writes powerfully about the connection she felt with generations of women before her as she stitched. Many women around the UK have felt the same creative drive in recent years, and their painstaking work has become a feature of women’s demonstrations. The single best known example is probably the Leeds Spinners’ elegantly embroidered Wrong Side of History My Arse, a design still available in various forms from FiLiA.

Our second woman on the frontline, Nomcebo Mkhaliphi, has discovered that taking pictures and sharing them on social media has become an important part of her work to encourage girls, and boys, to talk freely and without shame about menstruation. If you are on Twitter/X you may well have seen the bold and positive images she posts from Estwani, formerly known as Swaziland. We are very proud to be able to give her a platform here, and to have more of her pictures to share.

For the next two weeks, Peggie v NHS Fife and Dr Upton looks set to dominate the headlines once again. This piece from The Times (share token) provides a useful summary of the background for anyone new to the case. The proceedings are being live tweeted by

.The button at the end of this issue takes you to our subscriber chat. As ever, you can also find us in real time on X/Twitter, at @DalgetySusan and @LucyHunterB, and our shared account @EthelWrites.

We are delighted that we can now plan for our fortnightly 21st century feminist publication to remain fully accessible to those who cannot afford a paid subscription well into next year. If you can afford a paid subscription, please consider getting on as it supports ALL women, including those like Nomcebo who are on low incomes or none, to be able to access The Frontline.

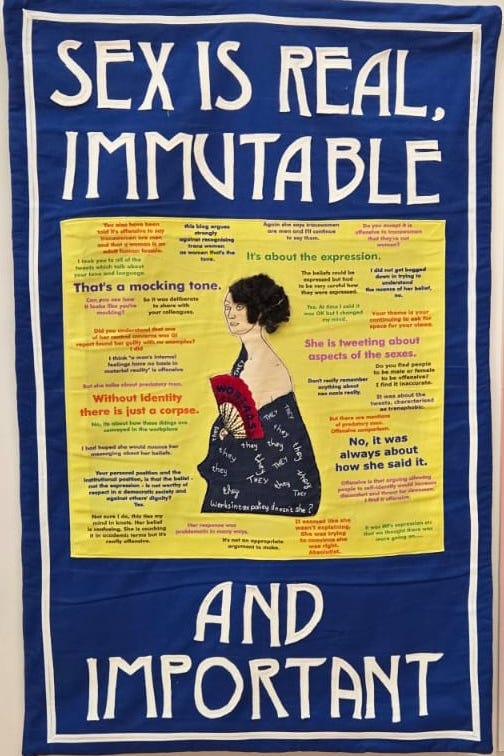

Material reality: a burst of creativity borne out of suppression and rebellion leaves a legacy of banners celebrating women who spoke out

By Jenny Reilly

Banner for Maya Forstater. Pic by Jenny Reilly

How do you hide a woman in plain sight?

You remove her name, forget her story, distort her words, replace her with a myth.

Joan McAlpine, Johann Lamont, Joanna Cherry, Maya Forstater, Kate Harris, Bev Jackson.

In creating five banners representing six women who have stood up for sex-based rights, my first objective was to ensure they were remembered. So little had been widely reported about what they had endured, or their successes, so it was easy to see how their pivotal impact could be forgotten. We've seen recently, how in the world where sex can be falsified, women's words can so easily be distorted and replaced - man with woman, male with trans, woman with cervix-haver, honesty with hatred.

I watched the world melt into post-modern theories where boundaries between reality and imagination suddenly became blurred. Headlines of women raping with ‘her penis’; thoughtless slogans chanted on repeat by our elected representatives; victims described as bigots; words reinterpreted as anything but how they were meant. Waves and waves of unreality, of turning things upside down and inside out. I needed something solid to hold on to. The banners would become the lifebuoys that kept keep me afloat

Detail from banner for Maya Forstater. Pic by Jenny Reilly

Our voices of dissent and reason bounced off the walls of our parliament, dying to nothing as vote after vote diminished women’s rights. Not valid! Unable to penetrate. Were our voices even real? I decided that banners like those produced by our foremothers were going to be our voice.

As I sat in my home stitching, mostly alone but sometimes with friends, I considered the women who had gone before. The women who'd stitched banners when fighting for their rights. Perhaps stitching as a group but more likely stitching alone, with stolen minutes, sometimes hidden but proud at being able to make a contribution. Running their hands across the fabric as their banners took shape. Threads squirrelled away in boxes to be kept safe, needles held closer to their faces as the hours wore on. I felt connected to these women, making the same movements, unpicking similar failures, beaming at work done well. My mother who first taught me to thread a needle, my great aunties whose eyesight diminished as they worked difficult long hours sewing the pleats into kilts. All the women who have put me right here right now.

Working on the banner for Johann Lamont. Pic via Jenny Reilly

I thought about the women represented in familiar works of art, some of them mythical, some of them real. The stories we didn't know. Did they push against the grain? Did they resent their place as an object in a man's bigger plan? Did they want more to be known about them? Those who modelled for the artists, their non-conformity, their likely exclusion from society. Did they rage or did they accept and revel in their fate? It was such a delight to include a reflection of an embroidered panel by Margaret McDonald Mackintosh in my final piece. Women had come so far, they were artists in their own right, not merely empty vessels to be manipulated by men. Progressive really.

Detail from banner for Kate Harris and Bev Jackson of the LGB Alliance, inspired by Margaret McDonald Mackintosh. Pic by Jenny Reilly

Detail from banner for Johann Lamont. Pic by Jenny Reilly.

As the fight for sex-based rights got uglier, more violent and more poisonous, I retreated to the beauty of what I was creating. The gold thread held in place with the tiniest of stitches. The strong, confident felt letters. The glorious sheen of silk against cotton. This was something real and tangible I was making, against a backdrop of unreality. I could touch the soft wool that my friend Caroline had felted, run my fingers across embroidered words, feel the myriad of textures layered one upon the other.

The process was often slow as I was teaching myself new techniques, I had never undertaken such a large and intricate project before. I watched videos of women passing on their embroidery skills. I unpicked, redid, unpicked, cut more fabric. I was often frustrated with mistakes, with fabric not cooperating, with pieces not looking right. However, I continued. I pushed on. Sometimes stabbing the fabric angrily with my needle as I remembered the gross unfairness of our situation. Other times the needle glided through, and the stich would land in exactly the right place. I didn't give up or reconfigure, I was determined to complete this project.

So here is my tribute to these women, what they achieved, what they endured and what we must remember. The red circle in Joan McAlpine's banner to represent the abusers who threatened her while sporting wee red circles in their profiles. Johann Lamont's goldwork sword where she sliced up the woolly use of gender with the sleek precision of sex. The mirror and yellow ribbon of Joanna Cherry's, reflecting the truly awful unfairness meted out to dissenters by the self-proclaimed party of fairness and equality. The ludicrous words picked out and fabric-printed onto Maya's, emphasising the witch-hunting nature of her sacking. The mermaid's tails trying to drag LGB Alliance into the abyss. These works are a testament to what we all went through in this extraordinary period.

Banners on display at the Women Create Festival, London, 30th-31st May 2025. Left to right: for Johann Lamont, Joanna Cherry and Joan McAlpine. Pic by Jenny Reilly

Banner for Kate Harris and Bev Jackson of the LGB Alliance. Pic by Jenny Reilly

Joanna Cherry (l.) and Jenny Reilly (r.) with the banner for Joanna Cherry. Pic via Jenny Reilly

I hope in years to come there will be lots of art and literature describing the fight women across the world undertook to ensure their rights and their reality. As well as being an intensely challenging period, there’s been a burst of creativity borne out of suppression and rebellion. Maybe my work will be displayed with others or maybe they’ll live in my spare room from now on, whatever happens, I know who joined me in this fight.

Jenny Reilly is a self taught textile artist who uses her craft to document the fight for sex-based rights in the UK. Her art incorporates traditional textile methods like embroidery, appliqué and needle felting, creating pieces that connect contemporary issues with historical narratives. She posts on X under the handle @crit_gen.

Jenny has asked us to donate her fee to Build a Girl, a not for profit Community Interest Company. They work with girls and young women at risk of sexual exploitation in Bradford, West Yorkshire, particularly those with few or no role models. Local survivor and campaigner Fiona Broadfoot and her team work to build intergenerational trust and friendship using positive female role models. They are currently fundraising for their 2025 Summer Programme of activities for girls aged 10 to 18. You can donate here.

From the moment I saw my school uniform stained with blood I wanted to be a voice for girls: breaking the cultural taboos and myths that lead to shame and discrimination

By Nomcebo Mkhaliphi

Nomcebo on her way to a school where she will distribute menstrual products

Every month, two billion women and girls across the world menstruate. It is a natural, healthy process, a key element of the female reproductive system. But for far too many women, menstruation is fraught with difficulty because of poverty and stigma.

Hundreds of millions of women and girls cannot afford menstrual products such as tampons or pads. Many do not have access to clean water or private toilets. And in some parts of the world, menstruating girls and women are still seen as ‘dirty’ or ‘untouchable’. Myths persist that stop menstruating women and girls from touching certain foods or from entering places of worship.

One woman has single-handedly set out to remove the stigma of menstruation in her part of sub-Saharan Africa, as well as distributing menstrual products to girls who have none.

Nomcebo Mkhaliphi lives in Estwani, formerly known as Swaziland, a landlocked country in southern Africa, bordered by South Africa and Mozambique. In this interview with The Frontline she tells of her campaign to make menstruation matter.

Can you share your personal experience with menstruation as a young girl in Eswatini and how it inspired you to start this campaign?

As a young girl growing up, I did not know anything about periods at all. When I had my periods, I had to use old newspapers and rags to protect myself during menstruation. I stained my school uniform and I was subjected to period stigma for a very long time. From the moment I saw my school uniform stained with blood, I wanted to be a voice for girls.

And I did not want my daughter to experience the same as I did. So, I would say having my children - two boys and a girl - is a motivation in itself.

What are the main objectives of your menstruation campaign in Eswatini’s schools and how do you measure its success?

I want to raise awareness and eliminate stigma. In my country, culturally you were not allowed to talk about menstruation, so what I am doing right now is to educate both girls and boys that periods are a natural, biological process. My main goal is to break cultural taboos and myths that lead to shame and discrimination.

I also want to ensure young girls have access to menstrual products. This is very dear to my heart because, as a young girl, I never had such an opportunity. Seeing smiles from the girls that I work with warms my heart.

Another of my objectives is to reduce school absenteeism. Most girls miss whole days, or do not attend certain classes during their periods because of shame, or the fear of getting their school uniform dirty because they do not have sanitary pads. But by distributing these pads, I am able to empower girls to attend school during their period without fear and discomfort.

I meet with girls at school and encourage them to talk about periods openly.

Pic via Nomcebo Mkhaliphi

Why is it important to include boys in your conversations about menstruation, and how do they respond to these discussions?

Involving boys is very important. It helps reduce teasing and the shame and embarrassment that girls often face at school. Also if boys are taught about this topic, it enables them to help their sisters overcome discrimination.

Boys learn to treat menstruation with respect which fosters empathy and equality. It shifts any negative mindset, helping build a more supportive society overall. Of course some feel awkward, shy at first, especially if they’ve never been taught about menstruation. Others are genuinely curious and eager to learn.

Can you describe a typical session you conduct in schools? What methods do you use to engage students and make them feel comfortable discussing menstruation?

As a person who always wears a smile and is passionate about what I do, there is no specific method that I use. Once I start having a conversation with the girls, often sharing my own story or explaining my mission, everything just flows. When everything runs smoothly, questions come up and there is a lot sharing of experiences, laughter and joy by the end of a session. The more we talk about periods openly, the more we normalise hearing about them. However, I do think the conversation about menstruation should start at home, that is still a big challenge. So many families face financial constraints and cannot afford sanitary pads every month. Women and girls are forced to use unsafe materials like old newspapers or old rags, so it is important that I can offer them menstrual products as well as discussing the issue openly.

Pic via Nomcebo Mkhaliphi

As a mother, how has your work influenced the way you talk about menstruation with your own daughter and sons and how do you handle criticism about your work?

With my sons, I have always been intentional. I teach them that periods are not a girl’s problem, they are a human experience. They know what menstruation is, and more importantly that shaming girls about periods is not acceptable. I want them to grow up as respectful, supportive young men who can one day be compassionate friends, partners or even fathers themselves.

The criticism and online harassment I get can be incredibly discouraging, but I stay motivated by constantly reminding myself why I started this work. I lean on my support system – my children - and also my Twitter/X family who remind me that I’m not alone and that the change I am fighting for matters the most.

Criticism often comes from fear or ignorance and I choose to see it as proof that the conversation is getting louder and reaching new spaces. It means we’re disrupting harmful norms and that is a good thing. Lastly, I make time for self-care. I allow myself space to feel hurt, but I do not stay there for too long, I remind myself that advocacy is a long journey, and every step forward, no matter how small, is worth it.

Pic via Nomcebo Mkhaliphi

What has been the impact of your work and what does the future hold?

I have been told by parents that their daughters are now able to speak up, girls now feel free to talk about their periods openly. My long term wish is to see all girls around the globe having access to sanitary products. I wish everyone, including world leaders, could see the importance of free access to sanitary products. It is not easy but it is worth it. They should know that education about periods changes everything. The more we talk about periods openly, the more we normalise hearing about them. One girl, one pad, endless possibilities! I want to see girls reaching their full potential. I want to see girls becoming leaders. I want to see girls shining.

Nomcebo Mkaliphi is from a small community in the southern part of Eswatini. She is from a family of four girls and one boy, and was the third born. Her parents and her elder sister are dead. She has two sons and one daughter and her volunteer work started as a desire to help one girl at a time, but now reaches thousands. You can find Nomcebo on Twitter/X @nomcebo_ mkhali and if you want to support her work you can make a donation here.

Atta girl! Remembering Britain’s Lumber Jills who kept the country supplied with timber during WW2

By Lily Craven, known to her many fans on Twitter/X as @TheAttagirls

Pic by nicooud79 via iStock

The Women of the Week are the 15,000 young women aged 17-24 who left home for the first time in 1942 to heed the call to join the Women’s Timber Corps (WTC), solving Britain’s desperate need for timber after Germany occupied Norway, our main timber importer.

The Lumber Jills - the name was coined by the Northern Daily Mail on 8 April 1942 after 25 Lancashire-born clerks, typists and hairdressers left Manchester for a timber training camp in the South-East of England - felled and crosscut trees by hand, operated sawmills, drove timber trucks and ran whole forestry sites. It was hard, dirty work, physically and mentally demanding, and they lived and worked in the most basic conditions.

In 1939, Britain imported 96% of its timber, a raw material critical to the war effort. Railway lines, telegraph poles, gun butts, ships, aircraft, packing cases for bombs and ammunition, charcoal for gunpowder, even pit props for the mining industry – they all depended on it. When WW2 began, imports faltered and after Germany invaded Norway in 1940, they stopped altogether. Just seven months’ supply of wood remained for the whole of Britain.

The government was resistant to employing women to fell trees but there were already thousands in the Women's Land Army doing their bit, so the official position became untenable. The Women's Timber Corps, a sister branch of the Land Army, was officially formed in April 1942. In May 1942, the Scottish WTC set up its own training camps at Shandford Lodge near Brechin, Angus, and Park House in Aberdeenshire.

Learning how to use axes and cross-saws

The camps taught women all aspects of the timber industry during a four-week course. They learned how to fell trees, and how to use axes and large cross-saws. The chainsaw hadn't been invented so it was hard physical work, dirty and dangerous. They also learned how to haul tree trunks and how to measure and carry out saw-milling, which meant cutting the wood into usable pieces. Women proved themselves fully capable of wielding 14lb axes, carrying logs, operating sawmills, driving lumber trucks, and calculating accurate production figures on which the Government relied.

Earnings were on a piecework basis and averaged between 35 and 46 shillings per week (£70 to £92 in today’s money), which was roughly comparable to a male forestry worker’s wage, but unlike the Land Girls who had a fixed wage and food and accommodation thrown in, the Lumber Jills had to pay their own expenses.

The English Lumber Jills had to find digs, some relocating as often as eighty times during their service, but the Scottish Lumber Jills experienced the most extreme living conditions. They lived in bothies or wooden huts in the forests where there was no such thing as a toilet or somewhere to wash. They used the streams instead and faced real hardships for long spells at a time.

Despite widespread scepticism and hostility - their uniform jerseys and trousers were serviceable but universally regarded as too shocking for any decent woman to wear - the Lumber Jills proved they were more than equal to the task. Scotswoman Bella Nolan challenged a foreman to a felling duel when he aired his poor opinion of women workers. She took one end of the cross-saw, he took the other, and by the end of that day, they chopped down 120 trees.

In August 1946, the WTC was disbanded. The women handed back their uniforms and were given a letter of thanks from Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother - but that was it, none of the grants, gratuities or benefits paid to women in civil defence or the armed services. Their jobs were given to prisoners of war and their records destroyed. The director of the Women's Land Army and Women's Timber Corps, Lady Gertrude Denman, resigned in protest. The Lumber Jills were not invited to attend Remembrance Day parades because they were not part of the fighting forces, yet their work was vital to Britain's war effort

Only recently has their contribution been recognised: a statue honouring them in Queen Elizabeth Park near Aberfoyle, Scotland; a sculpture called Push Don't Pull in Dalby Forest, North Yorkshire, and a memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire to the Lumber Jills and their sisters-in-arms, the Land Girls. And in 2008, surviving Lumber Jills were finally recognised by the government and awarded a medal.

As one recalls: “The attitude was that women can't do anything. You could see it on the men's faces. But they grew to get the idea. We just got on with it.”

In her misspent youth, Lily Craven spent 28 years in prisons in England writing risk assessments, operational orders and contingency plans. Now retired, she spends her time finding ordinary women whose extraordinary achievements were buried in dusty footnotes in history books and writes about those instead.

Read more about Scotland’s Lumber Jills here and this BBC article tells the story of the work they did across the country.

Navigate the public policy maze with the editors as they keep a watching eye on the issues affecting women

Pic by: akinbostanci via iStock

We are all busy, so it is hard to keep up with what people in power are up to - particularly in relation to policies and services that affect women and girls. We can’t offer a full monitoring service, but in each edition we will highlight a few things to watch out for, and where you can find more information.

The Scottish Parliament and the Northern Irish Assembly are now in recess. The Senedd and Westminster go into recess next week.

The Welsh Government has just opened consultation on a National Strategy for Preventing and Responding to Child Sexual Abuse, closing on 8 October.

In Scotland, government-funded charity Engender has published a report into the experience of women in politics. We will be taking a closer look at this next month.

At Westminster, a joint meeting of the Commons Women and Equalities Committee and the Joint Committee on Human Rights held a pre-appointment hearing with the Chair-designate of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, Dr Mary-Ann Stephenson on 1 July. They have taken the exceptionally unusual step of recommending against her appointment, following a letter writing campaign against her: the Committees’ letter should be published here. MBM Policy’s analysis of how her treatment compares with other recent candidates for the post is available here.

Each legislature across the UK has a helpful ‘what’s on’ section on its website.

Northern Irish Assembly (click on “View full agenda” for the detailed forward look) Recess dates: 5 July 2025 to 31 August 2025

Scottish Parliament Recess dates: 28 June to 31 August 2025

Senedd Cymru | Welsh Parliament (click on “View full calendar”) Recess dates: 21 July to 14 September 2025

UK Parliament Recess dates: 23 July to 31 August 2025 (Commons), 25 July - 29 August 2025 (Lords). The Conference recess runs for four weeks