ISSUE 2: The Frontline

A 21st century feminist publication where women's voices have power

The power of women. Pic by Drazen Zigic via iStock

Issue 2 of The Frontline arrives with a bang. We kick off our occasional feature Why I Write with the formidable and fearless Julie Burchill. We are still recovering from the shock of her saying yes to our brassy request.

Women on the Frontline starts another occasional series, this time on the theme of mothers raising boys. In the first of two parts, the mother of a young son recalls the very start of their journey. Her story is followed by the frank reflections of Marlyn Glen, who was elected to the Scottish Parliament in its early years. Marlyn writes powerfully on the reality of life at the centre of power and how her early hopes for the Parliament as force for improving women’s lives. Were they realised?

Our Woman of the Week is Margaret Nevison, whose work in the poorhouse system led her to use playwriting to draw attention to how marriage stripped women of their rights, all too often leaving them trapped in poverty and domestic violence.

And we have started Readers Respond where we will highlight some of the most interesting feedback from readers. This week the topic is endometriosis.

The button at the end of this issue takes you to our subscriber chat. And as ever you can find us in real time on X/Twitter, at @DalgetySusan and @LucyHunterB, and our shared account @EthelWrites.

Thanks again to all our subscribers for joining us. With your support our fortnightly 21st century feminist publication, where women's voices have power, can stay fully accessible to those who cannot afford a paid subscription, without expecting our women writers to work for free. For those who have asked about making a one-off donation, please email us and we can let you know how.

Julie Burchill was recently described by Julie Bindel, no mean writer herself, as the best writer on this island. In the first of an occasional series, Julie Burchill tells us why she writes

By Julie Burchill

Pic by Marcus Winkler via Unsplash

I always wanted to be a writer, for as long as I can recall having to name what I planned to do when I grew up. My parents were factory workers, my friends aspired to work in offices; I didn’t fancy either. What did I like, as an adolescent feeling the creeping pressure to make plans for incipient adulthood? Not much, except pop music, masturbation, reading and being rude to people. That was it; I could be a writer, and get paid for being rude to people, like Dorothy Parker.

I presumed it would be easy, as I considered myself so clever. So what if I could name only one working-class female writer - Shelagh Delaney? So what if my bright, attractive friend, on telling the school careers officer that she fancied becoming an air stewardess, was mockingly told to ‘come down to earth’? So what if my mum, popping her head around the door to see me bashing away on my precious old typewriter, would inevitably inquire how my ‘typing practise’ was going? To say that there was poverty of expectation in my social group is like saying Tabasco is spicy; my classmates, through no fault of their own, made the average pit-pony look like an aspirational high-flyer.

Still making a living

Reluctant to get a job, with a heavy heart I returned to school for my A-Levels, sure that something to do with word-wielding would turn up - and within weeks, at the age of 17, I was indeed earning my living as a writer, albeit a living so humble that many a morn saw me scrabbling in public waste bins hopefully looking for glass pop bottles which might be returned to a corner shop and the combined pennies one received in return used as bus fare. I was 17 and working at the extremely popular and influential New Musical Express; I’m now approaching my 66th birthday, when I’ll become an Old Age Pensioner, and I’m still making my living as a writer. I couldn’t have loved it more.

It didn’t work out quite like I thought it would. I imagined I’d write some exquisite masterpiece of a novel, along the lines of F Scott Fitzgerald, but coarsening my budding talent so early and thoroughly in the mercantile word of journalism put paid to that. I became addicted to the instant gratification of the showing-off and the deadline and the pay-back; looking back, I can’t imagine any life that would have suited me better, certainly not the cloistered life of the serious novelist. I did write fiction - a number one bestselling dirty book, Ambition and Sugar Rush, a Young Adult novel that was made into an Emmy-winning TV show, and I enjoyed that well enough. But journalism is what I do best.

“Are you still writing?”

Why do I write? Because I can - in both senses of the word. I know I’m really good at it, so it would be a shame not to. And because, now I’m an invalid, unable to walk and in a wheelchair, I’m blessed that my hands still work. In the five months I recently spent in hospital, writing was a good part of what kept me from losing my mind, as well as my legs.

It was quite the lesson in humility being a patient for so long and being looked after by mostly very young nurses. I was apprehensive at first that, as I’ve got such an awful anti-Woke reputation, some of them might take a dislike to me or even refuse to treat me; in 2023, Teresa Steele had her hospital surgery cancelled after she complained about a transvestite nurse, and requested that she only receive intimate care from women. I was brought down to earth with a bang by the fact that only a handful out of maybe a hundred health workers I encountered even knew who I was! I’ve had it in the wider world, too. ’Are you still writing?’ are the most painful words a scribbler can hear; they became familiar to me, alas, during my tenure as a columnist at the Telegraph, which at the time had an ageing and dying readership. It was a far cry from my commercial glory days of the 1980s when as a Mail On Sunday columnist I witnessed my mother cry out with alarm as I was given a prime-time television commercial. ‘That typing practise paid off, eh, Mum?’ I couldn’t help smirking.

Now I write mainly for the Spectator online. But what I’ve lost in fame and money, I’ve gained in knowing that my writing is immeasurably better than it was back then. It’s good to know, too, that I was a young journalist at a time which rewarded me with enough fun and money to last nine lifetimes. It’s not like that now, for reasons including the internet doing severe damage to newspaper sales and the rise of nepotism and the box-office-poison ‘hereditary column’.

I write because I’m good at it. I write to make my living - how beautifully ambiguous that phrase is. I write because it’s all I can do. I write because it takes the pain away. I write because speech is my second language. I write because sometimes, if you’re lucky, it feels scary, like you’re about to cross a high-wire without a net - and then, if you’re really lucky, you fall, and you fly. That’s why I write.

Julie Burchill has been a published writer since the age of 17 - she will be 66 next month She is currently seeking a publisher for her memoir 'Halfling: A Farewell To Legs'.

She has asked that her fee is donated to “a fighting fund for defending women victimised by cross-dressing men”, which we are delighted to do. We will be donating it to Tribunal Tweets, whose volunteer team do such important work.

Editors’ recommendation: Professor Selina Todd has written a “splendid and illuminating” (Kate Kellaway, The Observer) biography of Shelagh Delany, Tastes of Honey: The Making of Shelagh Delaney and a Cultural Revolution (Chatto and Windus 2019)

Boy Mum (Part 1): Anticipation

By Bertha Dalziel *

Tiny Son, with Cloud the dog (disappearing top right ) Pic by Bertha Dalziel

My son (known as Tiny Son to a few people on the internet) is four now, nearly five. He frequently asks me how many days until his birthday, eyes widening at the unimaginable stretch of time. "60 days?!" Like an astronaut contemplating deep space from his rocket ship.

He was a Covid baby, born in that strange time when the whole world seemed muffled and everything stopped. My husband and I had moved to the Netherlands long before I got pregnant. I wasn’t working and this probably added to the isolation I felt as everyone retreated into their homes. Life seemed in abeyance for everyone, but especially me.

The first weeks of pregnancy brought hyperemesis, causing severe nausea and vomiting. I offer up the hope here that if you have a child you never experience this condition - being dragged backwards through the gates of hell is preferable. I retreated to my bed in a surge of pregnancy hormones to watch Super Vet, my husband coming into our bedroom to find me in paroxysms of grief, the eventual explanation for which turned out to be... "there was a penguin".

The pregnancy

Things stabilised and I dutifully attended the few brisk, practical midwife appointments that are recommended in the Netherlands, sitting across the desk from a series of brisk, practical midwives. I answered all the questions that one would expect, about blood pressure and so on, and others that gave a grim insight into what life is like for too many women ("are you worried your partner might hurt you or your child?").

At 20 weeks, I went by myself, as per Covid rules, to get the scan. I thank God I didn’t realise this is the one where they check for abnormalities; I had enough nebulous worries I was suppressing without anything concrete to hang it on. The scan was fine, the baby described as 'lively' (oh, how the years have proved that true) and I got a photo to take home.

It’s a boy!

We didn’t want to know the sex, as we said it wouldn’t make a difference. In truth, we were completely unprepared and anyway, I quietly and very feministly proceeded on the assumption that this was surely a girl as it was so pretty a child. Twenty weeks later, and much to my eventual surprise, that is when I was sufficiently down from my hormones and hospital drugs to have as coherent a feeling as ‘surprise’ on anything, I gave birth to a boy.

Now, I am the oldest of three girls. My whole childhood was us girls, and friends, also overwhelmingly of the female persuasion, trooping in and out of our house. My dad is a gentle, irony-tinged presence in our lives, while our mum is very much ‘In Charge’. Any boys who crossed the threshold had to suffer the mild indignity of my Aberdonian mother absen-mindedly including them in the collective "girls, girls" when she wanted the group's attention (in her accent - "giruls, giruls").

My husband, by contrast, grew up in a traditional working class family with a more even split between the sexes and a low-key conservative take on the attendant social roles. This was the second surprise for me on having a boy: my family genuinely weren't fussed either way (though my mum was initially slightly worried what we would do with a boy in the family), but my in-laws were completely delighted that I had produced a son. I will never forget coming down the stairs at my in-laws’ house one day to find my mother-in-law spray painting the pink pram I had bought grey. Yes, really. She even had a visor on. Other people's families are a mystery, even when you marry into them.

So, adjusting to the idea of a boy was more tricky than expected. And that was just within the family, which settled in time. The experience of being the mother to a small boy lay ahead…

Bertha Dalziel is a pen name for a perennial expat who is dipping her toes into her forties. She became a mother while living in the Netherlands and a stay-at-home mother by accident. She has recently returned to Scotland and is enjoying it enormously, much to her surprise. She can be found messing about on X under @BertDalziel when she should probably be doing something else.

Boy Mum (Part 2): Experience will be in Issue 3 of The Frontline, out on 4 July

Ogino Ginko’s piece in Issue 1 on the difficulty of getting a diagnosis and treatment for painful, disabling periods resonated with readers. An older fellow sufferer described the response of "yeah, it's probably endo, but the treatment will still be painkillers and cracking on, so do you REALLY want the invasive tests?"

Another noted that a delayed diagnosis makes it more likely the treatment offered will be “extreme drugs and/or extreme surgery as research into more specific treatments is limited as funding is so sparse,” adding “Some prescriptions, eg pill for non/undiagnosed conditions may mask what’s going on and worsen damage that builds over the years.”

Another commented that “being listened to and believed is an immense relief.” Frustration that “women's health simply doesn't get paid enough attention” was a common theme.

Kirsteen Sullivan MP, chair of Westminster’s All Party Group on Endometriosis responded, “It’s a no brainer that earlier diagnosis (for some women) can help prevent worsening of conditions that end up requiring more complex surgical interventions. Shorter diagnosis times is a must for both the physical & mental health of women and for less invasive treatment options.”

Life as a woman in politics is hard work and can be disheartening but we need more women in parliament to stand up for our rights

By Marlyn Glen

Voting With Our Feet - a protest by Sole Sisters, made under Covid-19 restrictions, ahead of the Scottish Parliament’s most recent election in May 2021. Pic by Rob Hoon.

On my first day in the Scottish Parliament following my election as a Labour MSP for the North East region in May 2003, I was handed my official pass with my name misspelt.

When I pointed out the mistake, the parliament official refused to believe me. Instead, he went off to check his official records. I quickly realised that the closer you get to what you might think of as the centre of power, the further away you feel. It was my first wakeup call. It was not to be my last.

Even so, in the spring of 2003, I truly believed that the Scottish Parliament would make a significant difference to the lives of ordinary people, and I was proud to be part of what was presented at the time as a great Scottish revival – particularly for women. At Holyrood’s first election in 1999, Scottish Labour had used constituency twinning and zipping to contribute to the historic breakthrough that saw 48 women (37.2 per cent) elected. When I was elected in 2003 there was a modest increase in the proportion of women MSPs, rising to 51 out of 129 MSPs (39.5 per cent).

As I settled into my new role, I asked to be a member of the Education Committee, naively thinking that my extensive background in education would count. I was surprised to be told that I had the wrong kind of experience. I was, however, very pleased to be made a member of what was then the Equal Opportunities Committee. I saw this as a chance to continue my interest in promoting women in the party and women’s rights in general.

I was also a member of the Justice Committee – a huge learning experience since I had no experience of the justice system. We visited prisons, including Cornton Vale, the main prison for women in Scotland, where many of the women reminded me of the girls I used to enjoy teaching. If any trans-identifying men were being housed with these vulnerable women, it was never mentioned. Back then, it would not have occurred to me to ask.

I was angry and frustrated at the parliament’s refusal to legislate on hatred against women because the equality groups giving evidence claimed that misogyny was so rife in the justice system that a mere addition to a bill would be meaningless. Twenty years later, Holyrood has still done nothing specifically to combat misogyny.

Sadness at 2004 Gender Recognition Act

As a member of the Equal Opportunities Committee, I had to scrutinise the 2004 Gender Recognition bill . I still vividly remember one evidence session where a woman sobbed quietly in the gallery as she listened to her husband’s testimony. I will never know her story. I am sad to say we never properly considered the position of the women I now think of as trans widows. Our consideration was limited to the relationship between the bill and divorce laws, and we were strongly pushed by supporters of the bill to see this as an issue for men obtaining gender recognition certificates, ignoring any impact on their wives.

Networks for women

One of my proudest achievements was helping establish the tradition of women’s dinners at Holyrood with Ann Henderson. We had often discussed the importance of networking and the lack of opportunity for women to connect with each other, and the dinners become a regular feature. Women’s political networking is so undervalued that the first all-women gathering in the Parliament’s dining room was presumed to be a charity event. A male staff member thought that he should be allowed to attend and had to be forcefully told no!

The speakers were always fabulous, and women loved the chance to network. Inspired by their success, our local Scottish Labour women’s branch copied the idea and we even managed to meet up outdoors for women’s picnics during COVID. The dinners continued until the current Parliament was elected in 2021.

The Scottish Parliament - a force for feminism?

So, after 25 years of the Scottish Parliament, can it be a positive force for feminism? There is now a good number of women elected, with 59 female to 70 male MSPs. But sadly, not all women are feminists, even if some say they are to their very fingertips.

There is a great deal of good work being done – often cross-party - and some excellent MSPs, but we still need many more women to stand for councils and for parliament. Thankfully in my own party, Labour’s policies for promoting the equal representation of women have been reclaimed after the reality check of the Supreme Court judgment clarified that men cannot take women’s positions.

Reflecting on my role as a legislator, there is a big difference between working with the best intentions and properly considering all of the consequences of legislation. On the 2004 GRA, I realise now that we were advised by groups who had hidden, long-term objectives to promote ‘trans rights’ at the expense of women, objectives of which we were totally unaware. Sadly, some current MSPs appear still not to understand this, while others wilfully ignore or actually agree with these misogynist aims. When I was an elected representative, I never dreamed we would see a time when men self-identifed as women, muscling into women’s refuges, sports, toilets and changing rooms, as well as being allowed into women’s jails and political positions.

The tight connections between the governing party and government-funded groups stymie meaningful scrutiny, and I would now be much more cynical of lobbying groups and committee witness choices. There are advantages in having a small parliament, but it is not helpful for everyone to be in each other’s pockets.

When he was First Minster, Jack McConnell said that in the absence of a second revising chamber, he needed the hard questions to come from his own backbenches. In recent years, however, we have seen an obvious, sometimes catastrophic, lack of scrutiny by MSPs of government business, and far too many policies promoted by cliques.

It is essential that all political parties and civil society ensure that their processes protect everyone’s rights including, of course, women’s. Feminist ideas and analysis are crucial to this and we need to continue promoting them, while supporting each other.

It is hard work, and can be disheartening, but just as in 1999, there remains a great need for women to fight for women in the Scottish Parliament.

Marlyn Glen was MSP for North East Scotland from 2003 to 2011, standing down after two terms for the sake of democracy, agreeing with George Washington on this point. While ostensibly retired, Marlyn now works behind the scenes with Scottish Labour Women’s Declaration, and with her local Labour Party as Women's Officer.

Editors’ note: The not-short and still unfinished history of protecting women in Scottish hate crime law

The Offences (Aggravation by Prejudice) (Scotland) Act 2009, a private member’s bill introduced by Patrick Harvie MSP, created new disability, sexual orientation and transgender identity hate crime ‘aggravators’ (religion was introduced in 2003), but omitted any new coverage for women.

In May 2018, the Bracadale Review recommended ‘a new statutory aggravation based on gender hostility.’ Age was added to the list in the subsequent Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act 2021, but the Scottish Government resisted cross-party pressure to add sex as a protection for women. Instead it included a power to add sex to the Act later, using secondary legislation.

In February 2021, it set up the Criminal Justice and Misogyny Working Group, chaired by Baroness Helena Kennedy, which reported in March 2022, recommending a range of new misogyny-related offences. The Scottish Government consulted on these between March and June 2023.

On 1 May 2025, the Scottish Government published the analysis of the responses to the consultation. The next day, John Swinney announced that there would be no new legislation on misogyny before the 2026 elections to the Scottish Parliament, but that the Scottish Government would bring forward an order adding sex to characteristics covered by the 2021 Act before the next election. The timetable for this is not yet known.

In England and Wales, there are five recorded categories of hate crime (race, religion, sexual orientation, disability and transgender identity). Only the first two of these are “aggravators”: on 18 June, the government accepted an amendment by Rachel Taylor MP to the Crime and Policing Bill, to extend the aggravators to all five. Women remain outside this framework, although the Home Secretary, Yvette Cooper MP, has suggested extreme misogyny may be brought in to work on extremism.

Atta girl! Margaret Nevinson, the early twentieth-century campaigner who used playwriting to draw attention to married women’s loss of rights

By Lily Craven, known to her many fans on Twitter/X as @TheAttagirls

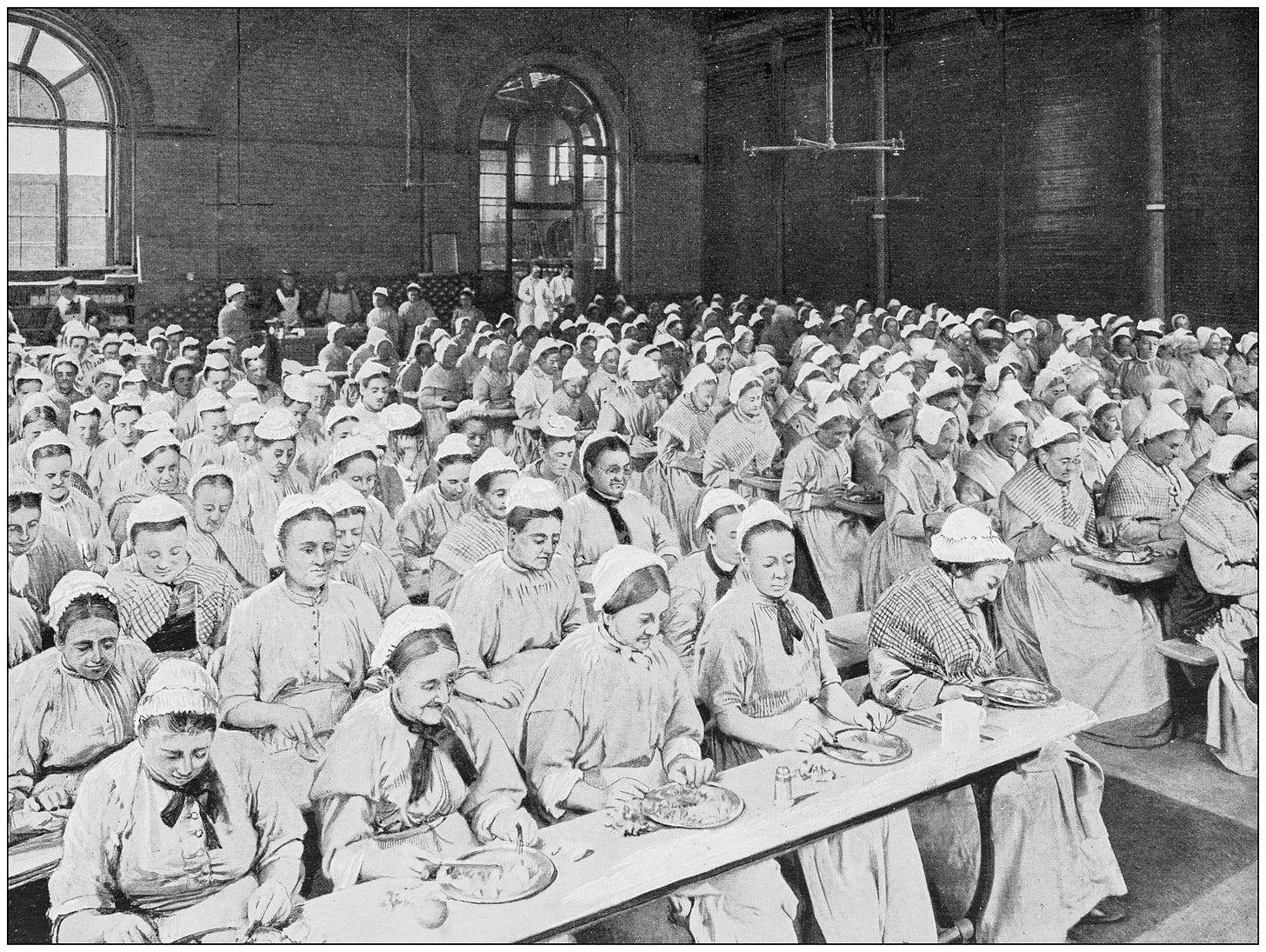

Dinner at St Pancras Workhouse, London (date unknown) Pic by: ilbusca via iStock

Woman of the Week teacher and suffragist Margaret Nevinson died in 1932, aged 74: Poor Law Guardian, first woman magistrate in London, playwright. The last bit caught my attention. She used her writing to highlight the many injustices of coverture.

Coverture was a Norman import. Anglo-Saxon women had the right to own property, but from the 11th century, a married woman was the chattel of her husband and property cannot own property. Everything a woman had - children, belongings, earnings - belonged to him. She had “no veto over or means of opposing” his decisions and if you’ve ever wondered why temperance was the earliest fight for women’s rights, this is why: when he drank away his wages every Friday, she couldn’t feed their children.

Born in 1858 in Leicester, Margaret was trapped in an unhappy marriage for 48 years. Her husband was often away. When he wasn’t, they ate separately except on Sundays. She refused to let it define her, devoting her time to the cause of women’s suffrage. Ironically, it was the only thing they agreed on.

In the workhouse

She was elected as a Poor Law Guardian in Hampstead in 1904, overseeing workhouses and allocating limited funds and assistance to the poor and elderly. It was the only elected position open to women in the days before women’s suffrage and she took a keen interest in the impact on women from working-class backgrounds.

On 8 May 1911, Edith Craig, daughter of Ellen Terry, staged Margaret’s play ‘In The Workhouse’ as one of a triple bill of plays at the Kingsway Theatre, Holborn. A one-act play based on a true story and set in the ward of a workhouse with religious texts on the “yellow washed walls”, its seven actresses wore “pauper dress: dark blue cotton gowns, ill-fitting, with white caps and aprons.” One character laments, “Doing time is better than this. Even in Holloway, ye runs round the yard and sees a bit of sky for an hour.”

Another character, Mrs Cleaver, is married to a taxi driver who lost his licence for being inebriated on duty and now the whole family is confined to the workhouse. A skilled dressmaker, she manages to find enough work to support herself and her children as well as somewhere for them to stay and applies to leave. The Board of Guardians refuses. She is legally under the control of her alcoholic husband. As he chooses to stay in the workhouse, so must she.

Penelope, a young single mother was “put off marriage at an early age” after her drunken father beat her mother to death. Her five children are all provided for by their fathers, but as an unmarried mother, she has full custody. “I’m going back tomorrow to my neat little home, which my lady-help is minding for me, to my dear children and my regular income, and I can’t say as I envies you married ladies either your rings or your slavery”.

Lily, a young woman expecting to marry her child’s father, changes her mind, saying to her baby, “I think we won’t get married, my pet! Better keep single, I say, after what we’ve heard tonight.”

Drawn from real life

The play wasn’t sensationalist or caricature or allegory. It was real life, drawn from Margaret’s experience of working with women trapped by poverty, hunger and domestic violence, and its message was clear: no matter what class you were, as a married woman, you had no rights.

Audience reaction was divided between those who applauded it for telling the unpalatable truth and those who found it offensive. The Morning Post (now the Telegraph) praised it, but The Times and the Daily Mail did not. One review with the headline: LONDON SHOCKED BY LEWD PLAY GIVEN BY SUFFRAGETTES claimed: "Votes for women's cause injured by a drama so coarse in theme and so perverted in moral that many prominent ladies withdraw their support."

Margaret pointed out, “The criticisms are strange and bewildering; only about five per cent have at all understood the point of the play…there is an air of injured innocence in the tone of some of the critics revolting and hypocritical to those of us who are prepared to face horrors if only we can reform these evils.”

“These facts told to a street corner audience invariably arouse great indignation, for the poor know by bitter experience that they are true; to bring them to the knowledge of our legislators is harder.”

The play sparked a debate in the House of Lords and so shocked the House of Commons that it legislated in 1913. Margaret noted with satisfaction that “the order by which a pauper husband had the right to detain his wife in the workhouse by ‘his marital authority’ is now repealed.”

Workhouses were not formally abolished until 1930. Coverture was knocked on the head in 1990 when women were finally taxed independently on their own incomes and given their own personal allowances. 1990. It only took 924 years.

As of 1997, around 10% of the people of this country had a genealogical connection to the workhouse system. I am one. My maternal grandfather was a “child pauper” in a workhouse in Liverpool. Responding to criticism of her play, Margaret said “The only apology I make is for its realism.”

In her misspent youth, Lily Craven spent 28 years in prisons in England writing risk assessments, operational orders and contingency plans. Now retired, she spends her time finding ordinary women whose extraordinary achievements were buried in dusty footnotes in history books and writes about those instead.

Navigate the public policy maze with the editors as they keep a watching eye on the issues affecting women

Pic by: akinbostanci via iStock

We are all busy, so it is hard to keep up with what people in power are up to - particularly in relation to policies and services that affect women and girls. We can’t offer a full monitoring service but each edition we will highlight a few things to watch out for, and where you can find more information.

On 17 June, an amendment proposed by Tonia Antoniazzi MP to the Crime and Policing Bill was accepted, disapplying existing criminal law related to abortion from any woman acting in relation to her own pregnancy at any gestation. The amendment’s wording, debate and voting on it are available here. The Bill has one further stage in the Commons (Third Reading) and then will go to the Lords for full consideration there. Follow its progress here. Abortion law is devolved to the Scottish Parliament. In August 2024, the Scottish Government set up an Abortion Law Review Expert Group, which is currently working on its final report.

Also on 17 June, the Scottish Government issued a consultation on what topics it should cover in the next Census. Deadline for responses 30 September.

A review into reform of the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive which is looking for responses on how “to improve the functioning and stability of the Assembly and the Executive Committee” closes on 30 June.

Senedd Cymru in Cardiff. Pic by Rixipix via iStock

Each legislature across the UK has a helpful ‘what’s on’ section on its website.

Northern Irish Assembly (click on “View full agenda” for the detailed forward look)

Scottish Parliament (click on “Read today’s Business Bulletin”)

Senedd Cymru | Welsh Parliament (click on “View full calendar”)