ISSUE 12: The Frontline

A 21st century feminist publication where women's voices have power

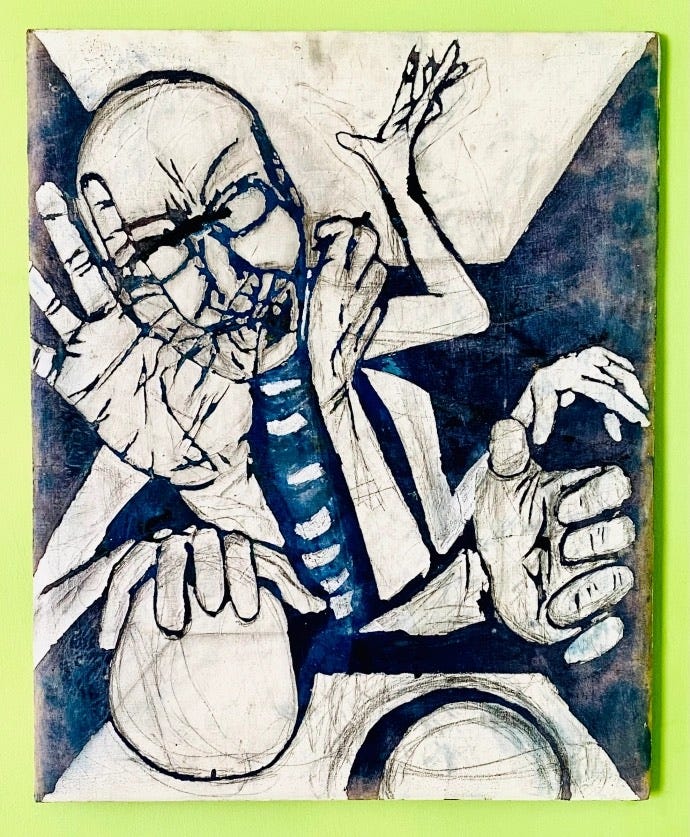

These are my hands. Pic via Sonya Douglas

In this edition of The Frontline Sonya Douglas writes movingly about finding her poetic voice and the intimate connection between her art and confronting the hard physical reality of her body.

Sonya is our first contributor from Wales, so this edition gives us an opportunity to raise the profile of women there who are campaigning for politicians and policy-makers to understand that the material reality of sex is foundational to women’s experiences and rights.

Women in Wales face a challenge familiar to those elsewhere: a government in office for many years persuaded to embrace self-ID and limited opposition to the policy in its legislature. Around the Senedd (‘dd’ is said like ‘th’ in ‘with’) is a small, closely-networked civic establishment, not unlike Holyrood in Edinburgh. But in Wales, women face an even harder task being heard than their sisters in Scotland and England, with a smaller local media, and they struggle to grab the attention of the wider UK one.

While the Welsh Government has not attempted to put through a Bill for gender recognition reform, it has used its powers in other ways to embed self-ID widely in policy and practice. This issue’s Policy and Power focusses on what’s happening in Wales and links to groups and resources from there.

Last weekend’s #199Days demonstrations were symbolic of how much of a struggle women in Wales still face. While the policing of demonstrations in London and Edinburgh (finally) meant they were able to go ahead without disruption, in Cardiff women were still faced with a close up aggressive counter-demonstration. As governments in London and Edinburgh consume women’s time, energy and resources by continuing to resist the rule of law, women in Wales need support too and we plan to publish more of their voices.

Continuing the Welsh theme, Woman of The Week looks at the five women being celebrated by Monumental Welsh Women, in a project to create the first ever statues of Welsh women in Wales. Before they started, there was no public statues in Wales commemorating the achievements of a real (rather than mythical) Welsh woman.

Ahead of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women on 25 November, and the start then of the UN’s 16 Days of Activism against violence against women, we also look at the Glasgow and Clyde Rape Crisis manifesto for sustained action on rape and sexual violence, launched last week.

The button at the end of this issue takes you to our subscriber chat. As ever, you can also find us in real time on X/Twitter, at @DalgetySusan and @LucyHunterB and our shared account @EthelWrites.

We are delighted that we can now plan for our fortnightly 21st century feminist publication to remain fully accessible. But we depend on some of our readers becoming paid subscribers so that we can pay our contributors, as well as keep the newsletter free so ALL women can access it. If you can afford a paid subscription, please consider getting one. Thank you.

These are my hands: As a poet comes to terms with her body she discovers there are no perfect bodies, no perfect existence, only real life

By Sonya Douglas

Sonya Douglas, poet and artist. Pic supplied by Sonya Douglas

I am a long time dying and grown old with waiting

hope never dies

these are my hands

I was 21 when I was finally diagnosed with scleroderma. Until then, I think, I’d just accepted that I was going mad. No one else seemed to feel their skin consisted of ground glass. None of my siblings had any trouble folding their arms or crossing their legs. I lived for those moments when I could lock my bedroom door and lie naked on my bed. Clothes were the enemy. It was weird but I was adept at masking.

It could be managed.

I would be fine.

And then one day the tip of my finger detached itself while I was temping, and I could no longer hide the fact that I was (literally) falling apart.

When you’re young standing out is alright in theory, but all you really want to do is feel like you belong. A gang, a cult, a cause; it was a shock to suddenly gain membership of the progressive rare disease club, a secret society that grew sick of itself as everyone grew sicker. Self-pity was meaningful, sympathy was not. I followed writers like Oscar Moore with avid trepidation, thrilling and lamenting at our unique insight. I chilled my friends with tales of unraveling fingers in the bath. I went for tri-monthly unlicensed infusions, and fully immersed myself in the embellishments of death.

And then, as the kids say, shit became real.

A leaflet about living with scleroderma mentioned almost matter-of-factly that the author lost her sight some years after diagnosis, and I plunged immediately into crisis. My father had lost his own sight some years previously and it felt like I was dealing with all my emotional trauma at once.

And so it’s come to this

My love, my sweet

The gods have decreed and you are to die

Moab, my child, my distraction

I bleed for you, my body, my red sun

Niiobid, the last, I beg you to listen

I am nothing without you, you will detach me from life.

From ‘The Dream Secret’ (1995)

The thing about fear is that it can be both paralysing and galvanising, but it took just one night of sedation to convince me the sometimes frighteningly messy uncertainty of real life was much to be preferred over a future numb with antidepressants.

I had always loved to write stories and poems, but it was now I truly began to write. I read the Book of Job which inspired The Dream Secret, a poem in four voices, which I recorded for the old BBC Made In Wales strand. It was at this point I first turned my back on party politics. There seemed something obscene in admiring sophistry and contrivance. Instead, I joined a Citizen’s Advice with a heavy refugee workload. I spent nights finding emergency accommodation for young women fleeing religious and social coercion, and most days navigating social services and the benefits system on behalf of our most vulnerable communities. Burnout was common and came early. When I left, I moved as far west as possible before hitting the Irish Sea.

In Pembrokeshire I founded an arts organisation while working with the youth offending team. I got pregnant and delivered Flying Start courses for young parents. I wrote projects for schools and community organisations, sidestepping into STEM promotion and tech innovations. Consistent throughout was the way I engaged with my own medical care. I studied not just my condition, but the effect it had on my own body systems. I became my own specialist, consulting with my doctors not as their patient, but the person with primary knowledge. I soon learned to tell who was confident in his skills, and who was simply relying on authority.

The lesson instilled: everything is a boundary. The things you care about, and the ways you care, and the things you choose to remember, and the things you will never share; and the things you can’t forget; that tension of fear marking before from after; and the unravelled skin; the moment that separates the light from the darkness: you get to examine, adapt and maintain these things.

So now I’ve come full circle.

These Are My Hands (1997) by Sonya Douglas

I’m back in Cardiff, back engaging with party politics, organising once more at community level. Showing my hands to all I meet.

When the Critically Speaking podcast decided to label me transphobic and erase my contribution on being black and Welsh, they little realised the refinement my sense of self had already undergone in the trial of holding my own with strangers. The realisation that they’d blacklisted me for not sharing pronouns just added to my determination. This was religious and social coercion of an order not seen before, and I was ready to resist.

My experiences have given me the perfect understanding of how it feels to carry an inner sense of being incongruent with material reality. I still scour old photos for the memory of manicures and fine motor skills. If anyone was likely to feel like they’d been born into the wrong body, it would be the person occasionally waking up shrink wrapped into her own skin.

I know just what it takes to show up in your own life when all you stand on is how much everything hurts. I know the shame and confusion of a body that refuses to match expectations, and I know there is strength to be derived from recognising we all feel a version of the same thing.

There are no perfect bodies.

There is no perfect existence.

There is only the paralysing lie with its sedative filter, or the galvanising truth, warts and all.

Real life.

I am fire stone and paper, heavy with potential

I am vengeful and fury

these are my hands

From ‘The Dream Secret’ (1995)

Artist and poet Sonya Douglas studied graphic design at Newport College of Art. She is married and lives in Cardiff.

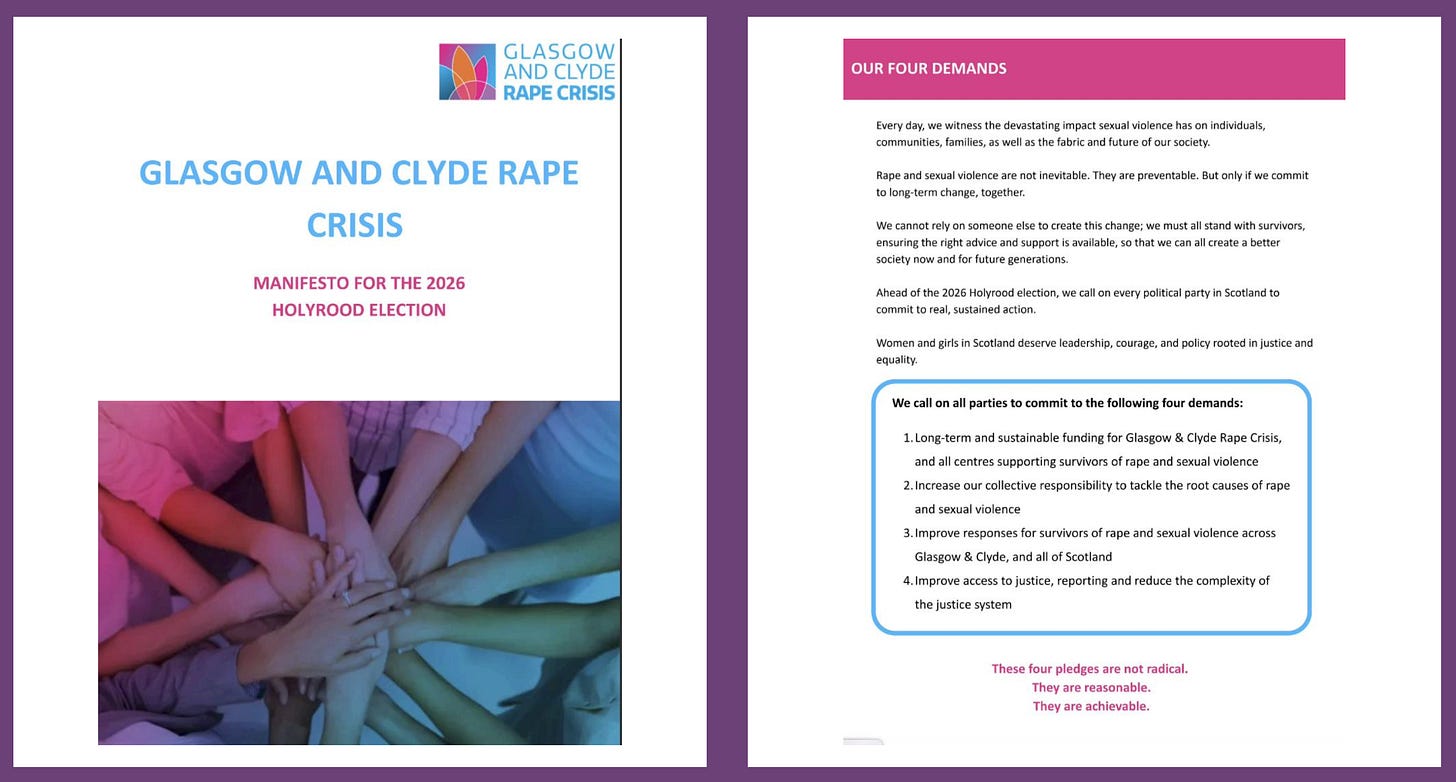

Glasgow & Clyde Rape Crisis Centre publishes its 2026 Manifesto with four demands for politicians to do the right thing and help end sexual violence against women and girls

By The Editors

Glasgow and Clyde Rape Crisis Centre (GCRC) has provided support for female survivors of sexual violence for decades. Last week it published its manifesto for the 2026 Holyrood elections, when Scotland, like Wales, will decide on the make-up of its devolved government.

Despite the courageous work of women across the UK over the last 50 years, sexual violence is on the increase. GCRC alone recorded 40,000 contacts with women last year – a 42 per cent increase from the previous year. The youngest survivor the centre supported last year was 13 years old, the oldest was 79. And across the UK, a woman is raped every seven minutes.

As the centre’s director Claudia Macdonald-Bruce says: “We are working to create a society where women and girls are equal and free from all forms of sexual violence. We’ve being doing this since 1976. Almost fifty years later, against the rising levels of sexual violence, I know we will be needed for 50 more”.

The centre’s manifesto is aimed at politicians in Scotland, but it is essential reading for every national and local politician across the UK. The manifesto’s four demands are:

Long term and sustainable funding: Sexual violence support services have been chronically underfunded sinch the UK’s first rape crisis centre was opened by second wave feminists in north London on 15 May 1976. Centres rely on a patchwork of short-term grants and voluntary contributions. GCRC argues for “multi-year, inflation proof funding models that recognise rape and sexual violence services as essential, life-saving public services, not optional extras.

Increase our collective responsibility to tackle the root causes of rape and sexual violence: As the manifesto points out, sexual violence is rooted in inequality between women and men, power and harmful social norms. Eradicating the root causes of sexual violence will require cultural change, through education. GCRC calls for a whole society approach with fully funded expert prevention work in schools, workplaces and communities. Change starts with what we say and what we teach.

Improve responses for survivors of rape and sexual violence: A survivor should never feel alone, yet current services are stretched thin. The manifesto asks for equitable access to high quality, trauma-informed services, which include specialist services for women and girls, black and minority ethnic survivors, and disabled people.

Improve justice reporting and reduce the complexity of the justice system. The centre highlights that one in four sexual crimes committed in 2024-25 in Scotland were recorded at least a year after they occurred. The justice system must focus on survivors’ rights and wellbeing, which requires better, trauma-informed practice and communications from police and prosecutors, increased protection in court, shorter delays, and a clearer, more accessible reporting process.

Click here to read the full manifesto and to find out more about the work of Glasgow & Clyde Rape Crisis Centre.

Atta girl! Not one but five monumental Welsh women who have made a significant contribution to the history and life of their country

By Lily Craven, known to her many fans on Twitter/X as @TheAttagirls

Pic via Monumental Welsh Women

Monumental Welsh Women is a not-for-profit organisation dedicated to recognising the contribution of women to the history and life of Wales. Until September 2021, there were no statues of real Welsh women in Wales. The project is working is on a mission to erect five statues honouring five Welsh women in five different locations around Wales in five years. So far, they have unveiled four statues: Betty Campbell in Cardiff; Elaine Morgan in Mountain Ash'; Cranogwen in Llangrannog’ and Lady Rhondda in Newport. There is one more in the pipeline - Elizabeth Andrews in the Rhondda. Read more here.

Sarah Jane Rees (1839-1916) of Llangrannog was a sailor on cargo vessels for two years, a Master Mariner qualified to command ships worldwide by 20, and edited a women’s periodical for “bluestockings and proto suffragettes” ironically entitled Y Frythones (The Bride).

As Cranogwen, her bardic name, she claimed the Crown prize at the 1865 National Eisteddfod in Aberystwyth for her satirical poem Y Fodrwy Briodasol (The Wedding Ring). Marriage, she held, clipped women’s wings.

Cranogwen’s work portrays sisterhood as a strong tidal bond of peace, comfort, and sunshine in a shady place, a balm for isolation, a bulwark against the barriers applied only to women. How fitting that she is the second of just four women honoured with a statue in Wales, soon to be joined by a fifth.

Five women of the week

That’s why there is no Woman of the Week. There are five. The thread that holds them together is their determination to blaze new paths so that we might follow.

First to be immortalised was Betty Campbell (1934-2017) of Butetown, Wales’ first black head teacher: a distant dream for a child who read Enid Blyton and dreamt of Malory Towers.

When she told her headteacher that she wanted to be a headteacher too, “I’ll never forget her saying ‘Oh my dear, the problems would be insurmountable’. Those are the words she used. I went back to my desk and I cried…But it made me more determined; I was going to be a teacher by hook or by crook.”

A pregnant Betty sat her A-levels, left school at 17, married at 18, bore more children, but “never gave up my dream of being a teacher”. When Cardiff Teacher Training College accepted women in 1960 for the first time - just six, mind - she applied. Her mother said: “Don’t be so bloody soft. You’ve got three kids. How are you going to do that?”

Sheer bloodymindedness, that’s how. Betty made the first six, taught in Llanrumney and took the first local headteacher vacancy. Her school became a template for multicultural education, an achievement cemented by her work for Black History Month, running workshops about Butetown’s contributions during WW2.

Betty’s statue is in Cardiff. The third statue is in Mountain Ash, South Wales, which honours author and scriptwriter Elaine Morgan (1920-2013) of Pontypridd. She won an Oxford scholarship in 1939, a remarkable achievement for a girl from the valleys but her first success was at eleven when ‘Kitty in Blunderland’ was published in the Western Mail. “I learned my trade in the era of snoek and Spam.”

Her scripts were the cream of 1970s BBC dramas. How Green was my Valley and Testament of Youth earned her two BAFTAs, Royal Television Society Writer of the Year, and Writers’ Guild honours, but she never forgot her roots.

She said: “I come from a working-class background in the South Wales Valleys… I wanted to convey the flavour of Wales; of people whose lives were just as dramatic and full of moral problems as any other lives.”

Elaine wrote The Descent of Women and gave worldwide talks, but her eye was firmly fixed on those invisible barriers.

“Economic liberation has turned into a kind of bondage for women because while it’s considered OK for them to go out and earn some money, they’re still expected to be responsible for all the shopping and cooking and cleaning and housework after they come home in the evenings and at weekends.”

Newport is where you’ll find the statue of lifelong feminist Margaret, Viscountess Rhondda (1883-1958), who used every opportunity to advance equality for women from all walks of life.

Marriage clipped her wings. Not for long. She joined the Women’s Social and Political Union against her husband’s wishes, organised its first ever meeting in Newport and invited Emmeline Pankhurst to speak. Emmeline sent her daughter Sylvia. He refused to let Sylvia in the house.

Margaret went on protest marches, jumped on the PM’s car, tried to set fire to a postbox. She refused to pay the £10 fine, refused to be bailed out by her husband, went on hunger strike at dilapidated HMP Usk and had to be released early. She was unstoppable, throwing herself into a flurry of initiatives advancing and promoting opportunities for women during WW1.

She wrote: “Nothing in the whole conduct of the War has been more striking than the readiness and the ability of the women in nearly all the belligerent nations to render invaluable service to their respective countries, and nothing has been stranger than the slowness of various Governments to realise the vast capacity of the resources upon which they might draw.” By 1922, she’d had enough of marriage. Helena Normanton, the first woman barrister, obtained a decree nisi for her.

And that brings us to the fifth candidate, awaiting her own statue: suffragist and tireless women’s rights activist, Elizabeth Andrews (1882-1960) of Glamorgan.

Elizabeth’s legacy is female empowerment. She testified before the Sankey Commission in 1919 where she advocated for pit-head baths to spare women the toil of washing coal-dusted clothes after a midwife of 23 years’ experience in the Rhondda told her that the majority of cases she had of premature births and extreme female ailments were those of women whose husbands are working night shift. She organised relief efforts during the 1926 General Strike and supported working women by spearheading the opening of Wales’ first nursery school in the Rhondda. .

Her memoir is entitled A Woman’s Work Is Never Done. She wrote: “It is they who have to bear the biggest brunt of the fight, with its poverty and worries, but they are facing it with that spirit of determination which makes for the true spirit of heroism.”

We don’t always appreciate the sacrifices of the women who came before us and so it is fitting that five of Wales’ finest are immortalised in this way. If you see one of their statues, please offer a nod of deep gratitude from me, won’t you?

In her misspent youth, Lily Craven spent 28 years in prisons in England writing risk assessments, operational orders and contingency plans. Now retired, she spends her time finding ordinary women whose extraordinary achievements were buried in dusty footnotes in history books and writes about those instead.

Navigate the public policy maze with the editors as they keep a watching eye on the issues affecting women

Pic by: akinbostanci via iStock

We are all busy, so it is hard to keep up with what people in power are up to - particularly in relation to policies and services that affect women and girls. We can’t offer a full monitoring service but in each edition we will highlight a few things to watch out for, and where you can find more information.

This week our focus is Wales.

After the Supreme Court (SC) ruling in April, the Labour-controlled Welsh Government put out what Labour Women’s Declaration Cymru (Cymru is the Welsh name for Wales) described as a “tepid response.” It is available here.

LWD Cymru said last week: “A promised statement from @WelshGovernment on the SC Ruling on women’s sex based rights is now overdue.” Instead, most Labour members and many others swiftly left the Senedd chamber as a plenary debate on the judgment got under way last week, leaving the chamber almost deserted.

Consultations have been put on hold and we are advised by women there that, in the run up to the May 2026 elections, Welsh Government business seems to be avoiding anything that will need them to recognise the outcome of the Supreme Court judgment.

Merched Cymru (@MerchedCymru on X/Twitter) and WRN Wales (@WRNWales) now both have representation on the Senedd’s Cross-Party Group (CPG) on Women, whose chair, from Plaid Cymru, is vocally pro self-ID. On Friday 14th November it will meet for the first time since its focus shifted from women’s rights generally to looking at ways to “increase diversity” in the Senedd and local government. The CPG on Women was a key driver of the abandoned Gender Quotas Bill which advocated for self-ID of sex, despite dissenting sex-realist voices, but has yet to discuss the implications of the For Women Scotland Supreme Court judgment. Information about the CPG is available here.

Some speakers from last week’s 199 Days demonstration outside the Senedd have posted their speaking texts, as the counter-demonstration was allowed to drown these out. The Speech That No-one Could Hear by

/@rowinggeek looks at the state of sport in Wales, and speaking notes from LGB Alliance Cymru (@LGBAllies_Cymru) are here.Last, Cathy Larkman has written here for WRN about The Legacy of Eluned Morgan, the outgoing First Minister of Wales. She wrote: “Just do it. Implement the Supreme Court judgment now. No more kicking the can down the road. Stand up to the activists and the lobbyists around you. Make this your legacy for the women and girls of Wales. Before it’s too late for you”.

Thank-you to women from Wales who helped us put this summary together.

Senedd Cymru in Cardiff. Pic by Rixipix via iStock

The UK Parliament (Click here for future business).

Northern Irish Assembly (click on “View full agenda” for the detailed forward look)

Scottish Parliament (click on “Read today’s Business Bulletin”)

Senedd Cymru | Welsh Parliament (click on “View full calendar”)